|

In-Depth

Breakfast With Rapaport

Martin Rapaport reviewed the state of the industry and hosted panels on diamond grading and responsible sourcing at JCK.

By Shuan Sim

|

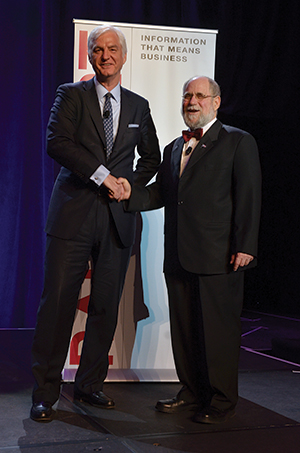

| Stephen Lussier and Martin Rapaport. |

After rousing the audience at the annual Rapaport Breakfast with a hearty “good morning,” Martin Rapaport dove straight into the state of the diamond industry, which he describes as being in a “critical period.” He peppered his presentation with technical details on the prices of rough and polished, provided an outlook on demand and supply moving forward and stressed the importance of all players in the industry from miners to retailers taking action.

Rapaport’s featured speaker at this year’s breakfast was Stephen Lussier, chief executive officer (CEO) of Forevermark and executive vice president of marketing at De Beers. Lussier’s speech focused on the consumer’s desire for diamonds and what businesses can do to understand that desire and profit from it.

Lussier called the allure of diamonds for consumers a “mystique” — diamonds are not only a luxury product, but represent the concept of luxury. Unlike any other luxury product, diamond marketing is rooted in stories. From being an expensive icon representing financial success to a gift that holds precious memories and even to a potential high-value investment, diamonds can represent many things. These stories fuel consumers’ desire, Lussier said.

“A diamond is forever,” the phrase used in the early De Beers campaigns, told those stories succinctly. Now that De Beers has stopped generic diamond marketing, it is imperative that companies keep the diamond story relevant to today’s changing consumer tastes. The key, Lussier said, is to find a simple but enduring message that captures the essence of a marketing campaign. Rapaport then took the stage to illustrate how to achieve that goal.

The challenge of marketing in the diamond industry, Rapaport said, was keeping the “diamond dream” alive today — specifically engaging young people commonly referred to as “Millennials.” To achieve that, the industry must defend the core symbolism of diamonds, instill a desire for “timeless luxury” over “disposable fashion” and work closely with technology.

Rapaport then said that to young people, synthetic diamonds are to natural diamonds like the Apple Watch is to the Rolex watch. The Apple Watch is a must-have because it represents the epitome of cool and the pinnacle of innovation, but cannot replace a Rolex watch, which tells a story of time-enduring craftsmanship. Likewise, natural diamonds carry with them a “geologic timelessness.” Rapaport called synthetic diamonds, which might appeal to Millennials, a “non-sustainable price competitor.” Technology moves along quickly and what may be technologically in vogue today, might be passé in a couple months, he said.

A way to appeal to Millennials effectively, Rapaport said, is to build strong brands. “Products are transient, stories are enduring,” he explained. Rapaport said that many retailers trying to reach the Millennial target group have been relying on outdated campaigns and it is time to update their strategies. However, the burden of reaching out to them should not lie solely on the backs of retailers. Even suppliers and producers need to do their part to help retailers become successful by reinvesting a portion of their revenue back into marketing.

Certain structural and political problems plague the industry, too, Rapaport said. He emphasized his previous stand on how too much Indian bank credit has led to over-manufacturing, resulting in rough prices superseding polished prices. “There must be a connection between rough and polished prices,” he said, adding that the Indian cutting market is in a self-feeding cycle where cutting has to keep going to keep credit lines open, regardless of whether the polished market can keep up. Rapaport recommended banks and financial institutions increase credit for the polished industry and he urged them to provide reduced credit for the rough.

Rapaport then predicted two outcomes: the first is for miners to forcibly lower rough prices to increase trade profitability. But that leaves the question of whether polished prices would follow suit and drop, which would be undesirable. The second outcome, he said, was to leave rough prices high, ultimately creating a shortage in supply and eventually leading to increased polished prices. However, the drawback of that outcome would be whether the desired polished price increase would arrive soon enough to prevent what Rapaport posits to be a “collapse of the diamond industry,” spurred by dealers unable to make a profit and eventually dropping out of business.

“The worst thing you can do is to do nothing,” Rapaport said. He explained that inaction allows the status quo to spiral out of control, and compounded with the threat that synthetic diamonds pose to the natural diamond sales, the industry is going through a very challenging time. Miners, manufacturers, retailers and financial backers of the industry would have to stand together to keep the industry intact, whether by creating an ethical hallmark for natural diamonds to differentiate them from synthetic diamonds, or by miners investing in marketing and the success of their dealers and retailers. The time of each individual minding his or her own business is becoming a thing of the past, Rapaport concluded.

A panel of representatives from grading labs, dealers and retailers joined Rapaport for the Grading Conference, immediately following the Rapaport Breakfast. Diamond grading reports have become increasingly important for dealers, retailers and even customers. Buyers are hesitant to procure goods that are not graded from an established laboratory, and today’s consumers have learned about grading terminology and are making specific requests for stones with certain characteristics. This trend has led to an increased scrutiny about the validity of grading labs and their methods, and ultimately, the impact that grading reports have on diamond prices.

The panelists included Susan Jacques from the Gemological Institute of America (GIA), Peter Yantzer and Jason Quick from the American Gem Society (AGS) Laboratory, Mark Gershburg from Gemological Science International (GSI), Jerry Ehrenwald from the International Gemological Institute (IGI), Dries Holvoet from HRD Antwerp, Cecilia Gardner from the Jewelers Vigilance Committee (JVC), David Lasher from the Diamond Dealers Club (DDC) of New York and Mahiar Borhanjoo of Venus Jewel International.

Jacques began the discussion by presenting the GIA International Diamond Grading System, introduced in 1953. Many of the American grading labs today use GIA’s grading terminology. Some in the audience asked why there was a need for multiple labs if most labs use GIA terminology and standards to grade diamonds. Jacques responded that the more pairs of eyes examining a diamond, the fairer the assessment. She emphasized that GIA had no wish to be the sole lab performing diamond grading and that each lab fulfilled a niche. Despite the differences, Jacques stressed a need for a coherent standard agreed upon by the various labs. GIA’s grading system simply happened to be that standard, having been an early benchmark in the industry.

The issue, said Jacques, was when labs use GIA terminology but do not apply GIA standards, which could result in what appears to be overgraded diamonds. She referred to recent developments where certain labs were issuing grading reports using GIA terminology with color or clarity grades a couple of levels higher than they would have been at the GIA or other labs. Gardner said that U.S. grading reports were governed by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), and intentional misrepresentation could result in a class action lawsuit or a civil suit. Legally, labs can use any grading system they wanted as long as they disclosed what system and terminologies they used in a manner that is understandable to the reader of the report. However, as GIA terms have become the accepted trade practice because they are so widely used, Gardner said, misrepresenting the GIA letters in grading reports harms the trust of grading labs.

Other attendees were concerned about conflicting grading reports and questioned who grades the graders: How do clients know that the graders are qualified? Most of the panelists representing labs agreed that while the methodology and equipment are standard across labs, the graders are human and some degree of subjective interpretation will factor into the grading. The panelists then assured that subjectivity was within an acceptable degree of tolerance, and most reports would not differ too much among labs — no more than perhaps one color grade or so. As to whether graders would be honest, the panelists said that relied on the clients trusting the labs to do their jobs based on their reputation.

A key issue raised during the panel discussion was that grading reports do not acknowledge the clarity grade sometimes known in the industry as “SI3,” which falls between SI2 and I1, when there is a great disparity between the two grades. This becomes pertinent when there is a large price difference between SI2 and I1 goods. Some in the audience were proponents of introducing a new SI3 clarity grade for the stability it would grant low SI2 goods that were above I1 clarity, but many of the lab representatives expressed no interest in introducing a new clarity grade. “I don’t think market forces should determine the grading standards,” said Jacques. “Grading should have nothing to do with value,” offered Ehrenwald.

Another issue brought up was why labs did not recognize the concept of “eye clean” in their reports — whether the flaws of diamonds could be visible to the naked eye given certain cuts. “How can you ignore ‘eye clean’ when it is more relevant commercially?” said Rapaport, who sat in the audience at the event. “Eye clean becomes a slippery slope, and is very dependent on eyesight,” said Jacques, citing the example of a younger person who has much better eyesight than an older person. Who would more likely be able to declare a diamond as not being “eye clean”? “And when that happens, where would the line be drawn?” Jacques asked.

“People get lost in grading reports,” Jacques said, when instead companies should focus on selling the story of the diamond and figuring out what it is that customers want. She said that retailers should be trying to help customers figure out what they can buy for their budget and which of the 4Cs the customer was willing to spend more money on.

While a number of retailers and dealers have demonstrated their commitment to ethical and responsible sourcing, many challenges and barriers exist in implementing those practices at all levels of the industry. A lively roundtable discussion ensued as members of a Responsible Sourcing panel questioned what could be done to overcome those impediments and achieve a business that people could be proud to say they are a part of.

Representatives on the panel from diamond trade associations and fair trade organizations included Edward Asscher from the World Diamond Council (WDC), James Courage from the Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC), Cecilia Gardner from the JVC, Dorothee Gizenga from the Diamond Development Initiative International (DDII), Douglas Hucker from the American Gem Trade Association (AGTA), Alex Popov from the World Federation of Diamond Bourses (WFDB), Kenneth Porter from the Alliance for Responsible Mining (ARM), Prakash Mehta from the Indian Diamond and Colorstone Association (IDCA) and Ronnie VanderLinden from the Diamond Manufacturers and Importers Association of America (DMIA). Representatives from retailers, wholesalers and financial institutes included David Bouffard and Philip Olden from Signet Jewellers, Eric Braunwart from Columbia Gem House, Mark Hanna from the Richline Group, Erik Jens from ABN Amro and Stephen Lussier from Forevermark. Rapaport was also on the panel.

One of the biggest challenges was how poorly defined the term “responsible sourcing” was, which made discussions difficult, much less outlining steps to take toward a solution. Having a loosely defined term also meant enforcing standards was an uphill task. Some of the panelists, however, disagreed with all the efforts placed on getting the definition right. “The vision, and not what is the definition, is what we should be focusing on,” said Braunwart.

Some of the panelists noticed that during summits and talks to promote responsible sourcing, vastly differing opinions about the matter often led to nothing being achieved. “I see a lot of sabotage,” said Rapaport. “There is a sense that since everyone in the world cannot agree to one thing, then everyone should agree to nothing.” He reiterated the need for action. “We are destroying our industry if we don’t do anything,” Rapaport said.

The Kimberley Process (KP), one of the early steps taken toward ethical and responsible mining, was brought up. Panelists hailed the early efforts of the KP in preventing the sale of “conflict diamonds,” but felt that the narrow definition of the diamonds — specifically, stones used to fuel war to unseat legitimate governments — had become ineffectual in recent times. Some panelists were frustrated that some of the solutions to address that shortcoming seemed to point toward starting from scratch. “We’re not starting over. It’s about building on and informing people about what’s already there,” Gardner said. “Why are we reinventing wheels?” she questioned.

As the discussion went on, ARM’s Porter brought up that a lot of work has been done by fair trade organizations and diamond producers and manufacturers, but a key component has been missing — the voices of laborers and miners. More has to come from them directly to make any meaningful progress in furthering responsible sourcing, he said, especially since these are main concerns of customers. Panelists agreed that there was a need to close the gap between reality and the expectations of customers when it comes to responsible sourcing.

Others felt that there was a lack of conversation among members of the industry. “You can do the right thing, but you also have to be seen doing the right thing,” said Gardner.

A possible solution raised was to have a chain of assurances at the company level, instead of a chain of custody on the diamonds. According to some panelists, the diamond itself didn’t do anything; it’s the companies that should come with an assurance that they did the right thing. When consumers know that these efforts are in place, then they would cut the diamond industry some slack, Rapaport said.

The roundtable was characterized by an active participation from the audience, many of whom were retailers with concerns about understanding and achieving fair sourcing standards. Some retailers were concerned that some of the standards set by fair trade organizations were out of the league for many small dealers. Panelists then said that a way to resolve that is rather than having a single, overarching standard for everyone to attain, responsible sourcing should come in gradated levels, like a ladder. The consensus was that fair trade organizations should be about helping their members achieve as high a rung within their means as possible, and when that is achieved, begin plans for helping them achieve the next level.

While many differences in opinions were voiced, the panelists felt reassured that the conversation was at least still continuing and that many players in the diamond industry were committed to better mining and sourcing practices.Article from the Rapaport Magazine - July 2015. To subscribe click here.

|

|