In return for a share of the profits, some producers are signing exclusive supply deals with large polishing firms and jewelers. But where does that leave the midstream players that still need rough?

Until recently, the industry was clearly divided into three sectors: The miners, which produce the rough diamonds; the midstream, consisting of cutters, polishers, traders and brokers; and the jewelers and retailers that sell the final product. But those lines are getting progressively blurred as mining companies seek to circumvent the middle market and reap profits all the way down the pipeline.

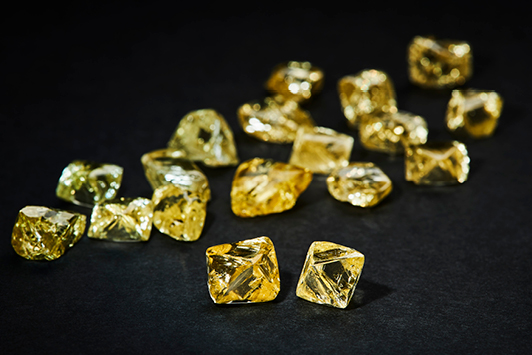

Within the last two years alone, Lucapa Diamond Company signed an agreement to sell all the rough from its Mothae deposit in Lesotho, as well as a large portion from its Lulo mine in Angola, directly to manufacturer Safdico, while Lucara Diamond Corp. inked a similar deal with HB Antwerp for its Karowe diamonds. More recently, Mountain Province reported it would sell its Gahcho Kué production to jeweler Chow Tai Fook. And niche miner Burgundy Diamond Mines has opened a manufacturing facility where it will cut and polish colored diamonds from its Ellendale site and third-party mines, then sell those goods into a supply contract with French jeweler Bäumer Vendôme.

These deals are not simply about crafting a reliable avenue for offloading rough even if the market slows — although that is a plus. Rather, they’re a lucrative way for miners to earn extra revenue, since most agreements entitle the miner to part of the profits from the finished product, whether it’s polished diamonds or finished jewelry. And on top of that, proponents say, this system makes for a sustainable, traceable and more efficient value chain.

Reaping what you sow

One reason behind this shift in business models is miners’ newfound appreciation of how much their goods can be worth. As recently as a few years ago, smaller independent producers didn’t fully understand how to value their product, comments Lucapa managing director Stephen Wetherall. Putting rough up for tender through brokers was the easiest way to get the highest price for your goods. But then, of course, the manufacturers that purchased the rough would sell the resulting polished for more than they’d paid, and the jewelers who bought the polished would further mark up their goods to make a profit.

“We, as miners, are far more knowledgeable on the entire diamond pipeline than we were, say, 10 short years ago,” says Wetherall. “We’re now starting to understand that there is value further down the pipeline, which you can’t get if you put your goods on tender and just sell to the highest bidder, who has no responsibility or onus to share anything with you.”

Burgundy CEO Peter Ravenscroft agrees. He sees no reason his company shouldn’t make a profit off the jewelry that contains his high-value colored diamonds.

“The retail of jewelry takes up over a quarter of the total value of the sector, so clearly there’s a profit margin in between polished diamonds and retail jewelry,” he says. This led him to wonder: “Why would that be the case, and why wouldn’t the producer of the diamond be able to share in some of that?”

But it’s not just about satisfying a mining company’s desire for greater financial rewards. It’s also about keeping stakeholders happy.

“You’ve got to think of it from the point of view of the ultimate custodian of the resource,” says Kieron Hodgson, executive director of the commodities and mining research division at investment bank Panmure Gordon. “If I’m the government, or the mines minister of Lesotho, and I hear that a mining company [that operates in my country] has recovered a 500-carat rough diamond, and they’ve sold it for $15 million, I’m very happy, because I’m getting tax, revenue and royalty payments from that. But if I then hear that that same 500-carat stone has been cut and polished into a 100-carat, a 50-carat [stone], etc., that has ultimately raised revenue of around $45 million, and I don’t have any rights or any way to benefit from the upside, I’m now no longer a very happy mines minister, because there is the sense that the country is not receiving its fair share.”

No tender feelings

This raises the question of why manufacturers or jewelers would want a supply deal when it means sharing half their profits. The answer is simple: The contract provides them with a regular stream of reliable, high-value diamonds in a tight market, and they don’t have to fight other companies at tenders for the privilege of owning them.

“If we had to go to tender, we wouldn’t win all the diamonds,” explains Brian Gutkin, CEO of Safdico. “We would win some of them, and we would like a chance at more.”

It also comes down to keeping their businesses financially liquid.

“Aside from guaranteeing [manufacturers and jewelers] supply, it also avoids them tying up working capital,” notes Burgundy’s Ravenscroft. When they buy a high-value diamond from a miner, “the process of manufacturing [the stone or the] piece of jewelry, and then finding the right customer and doing the sale, can take months or even years” — a long time to wait to recoup the money they spent on the original rough. “So that’s capital tied up in the diamonds themselves.”

However, with the supply agreements, the jeweler or cutter doesn’t pay the miner for the rough until it sells as either a polished diamond or finished jewelry, at which point the miner receives its stipulated share of the profits. In the meantime, the capital that would have gone toward buying the diamond is free for other business needs.

Hogging the goods?

With just a few players commandeering a large swath of the available rough, there may be concerns about shortages for the rest of the industry. Current rough production is already at an all-time low, with Bain & Company predicting that output won’t return to pre-pandemic levels for at least a decade.

On the bright side, it’s relatively unlikely that further miners will be entering exclusive deals, experts say. For one thing, supply agreements only make sense for mines that yield a certain type of diamond — particularly large, high-value stones — which eliminates most of the remaining producers as potential partners.

Indeed, for some of those remaining producers — such as Gem Diamonds — being the odd man out has its benefits.

“In a very simplistic assessment, if we have four high-value producers, and three have allocated their production to a single buyer [each], in effect, you have three buyers taking 75% of the supply,” says Hodgson. “So if I’m that fourth miner, and I’ve got, say, 50 buyers, and I’m 25% of the market, those 50 buyers are going to be paying me a much better price,” since there’s more competition for the goods and fewer producers offering them.

“You’re seeing the supply side of the equation reduced without your intervention,” he elaborates. “The other market participants have made your economic case stronger without you having to do anything. And this is before considering [that buyers who already have] purchase agreements may still be in the market acquiring [additional] goods.”

The consolidation conundrum

Once the deals are done and the dust settles, where does that leave the uncoupled dealers, jewelers and manufacturers? Will there be enough goods to support all these midstream players, or will they be cut out of the equation? It depends whom you ask.

Hodgson believes the market will consolidate, and peripheral operators will fall by the wayside.

“It’s no different from car parts manufacturers, engineers, or any other industry. If there are too many interested parties throughout the value chain, it’s inevitable that a few big players will rise to the top, and the rest will sort of fall through the cracks. Unfortunately for many, they will become collateral damage.”

Lucapa’s Wetherall also thinks market contraction is inevitable, but sees it more as a trade-off for necessary change.

“I think every industry sees change, and you’re going to have old structures replaced with new ones, and you may well see consolidation of various sectors within the diamond pipeline,” he says. “I think you’re going to see unintended consequences, with certain brokers, dealers, and small manufacturers potentially not seeing production and having to rethink their strategies. But you have to weigh it up with the flipside, which is that I get to continue to employ 400 people at the mine sites, and I’m able to extend my mine life by attracting additional value, and I’m able to contribute to the communities around us and uplift them, and I can contribute to the governments in countries where we do business. So yes, it would be very, very sad that there may be some people who find themselves replaced or removed from a changing environment, but I also have a responsibility and onus to try and ensure we contribute for as long as possible.”

Gutkin, meanwhile, doesn’t believe the goods coming off the market will be substantial enough to make real waves in the midstream. He also notes that a portion of the rough Safdico gets through its supply contracts with Lucapa actually goes back into the market, as the company picks out the diamonds it wants to manufacture and tenders the rest.

“I would say that [in the] big picture, maybe $250 million to $300 million a year is being sold [through supply deals], out of a total of perhaps $8 billion,” he says. “It’s miniscule. In the long run, it’s not going to affect the market. It’s too small.”

Mike Aggett is one of the middlemen whose business relies on getting hold of enough rough. The CEO of tender house Trans Atlantic Gem Services (TAGS) does not have an exclusive supply partnership with any miners, but he hasn’t noticed any shortage of available diamonds at his monthly sales, either.

“These businesses with supply contracts might cherry-pick a portion of the goods for themselves, but how big is that proportion in terms of all the goods that are coming to market?” he points out, echoing Gutkin. “And anyway, I think these things have a way of regulating themselves.... People rush down a route for a while because it seems like the thing to do, and then slowly, over time, it sort of disperses and softens, and while we don’t get back to where we were exactly, things get better, and the market can usually ride it out.”

Nonetheless, if the trend continues or if more companies decide to get in on the action, “it will certainly have an effect,” he acknowledges; it’s just “hard to tell what the long-term effect will be.”

A boon to efficiency

While losing some of the midstream isn’t ideal, producers do see supply deals as a way to create efficiency in the pipeline — and greater efficiency ultimately leads to a better market, they contend.

“The people who are producing the diamonds in the first place can be selling them to the end customer,” says Ravenscroft. “The middle chain is not really important as long as you can control your own rough, because you’re controlling the chain of custody all the way through. I actually think it’s a better model.”

This also addresses the hot-button issue of traceability. Having a more direct line from miner to retailer makes it simpler to pinpoint a diamond’s source, as the stone passes through fewer hands.

Wetherall, too, believes this system will improve efficiency — not to mention profit margins. “One positive, obviously, is the shorter amount of time a diamond spends going from rough mine gates to a consumer finger, and the shorter amount of time required for financing the value of the diamond until it’s sold,” he says. “And with fewer players in the industry pipeline, I think it will generate higher margins, and with those higher margins, we will be able to reinvest in the industry and the pipeline, to continue to make it more efficient.”

Avenues of change

What can midstream players do to keep from getting nudged out? Change seems to be the operative word.

“I think it’s going to force the middle to pivot, to rethink their situation and how they operate,” says Aggett. “If their supply is diminishing and their overhead is remaining the same, they’re either going to have to stop doing the work they’re doing, or find ways of getting more supply, but I think it’s inevitable that they will have to change.”

One option is to get in on the action, he observes. “I wouldn’t be averse to making a supply deal myself. I mean, Chow Tai Fook can’t be using all the rough they get from Mountain Province. So...I should probably be thinking about tying up with Chow Tai Fook and saying, ‘Let me tender all the diamonds you don’t need.’ You’ve got to look for where the opportunities are.”

Image: Burgundy DiamondsArticle from the Rapaport Magazine - April 2022. To subscribe click here.