Zvi Yehuda is a man of few words, but his accomplishments in the diamond industry speak volumes. The 82-year-old Israel native is the creator of numerous inventions that have changed the face of the trade, and even the face of diamonds themselves.

Yehuda first learned about diamonds in 1953 as a precocious 16-year-old. His father, wanting to break into a sector that was closed to those not born into it, hired an insider to give eight people a private lesson on diamond cleaving. Yehuda realized he could recycle the diamond dust created from bruting, clean it, and sell it back to diamond cutters to use for grinding.

With no formal training — just a head full of ideas and a brazen confidence — he took his concept to the head of Israel’s Industry Ministry. The minister, noting Yehuda’s youth, suggested he send his father in to pitch instead, but his father insisted that Yehuda be allowed to present his own idea. After witnessing a demonstration of the boy’s recycling abilities, the minister commissioned a factory for him, which Yehuda ran for three years before leaving the government to open his own business together with his father.

At the age of 23, Yehuda would go on to introduce the first set of digital scales for diamonds, and five years after that, he created the first diamond laser-cutting machine, along with a number of other inventions.

‘They are like my children’

While his ideas just seem to come to him, picking the one he feels changed the industry the most is a much more daunting task.

“They are like my children,” he says, “If you ask me to choose which of my four kids I prefer….” He stops, shaking his head.

When pressed, he and his son Dror — who runs the business and helps his father execute his ideas — get into a friendly debate over which innovation has had the biggest impact on the industry. Dror believes it’s the clarity enhancement process his father invented, which vastly improves a diamond’s optical properties to the naked eye.

“Every diamantaire dreams that one day he will walk in in the morning, open his safe, and all of his diamonds will suddenly be D-flawless,” Dror remembers his father telling him when he asked how he had come up with the idea for the clarity-enhancing chemical and its insertion method.

“It had such a huge impact on the industry at the time,” Dror continues. “For 30 years, it was a way for thousands of jewelers around the world to make a living and to sell diamonds with imperfections that they ordinarily would not have been able to sell for as high a value.”

A moment later, though, Dror contradicts himself, stating that the color meter his father created in 1977 for rough diamonds was his greatest invention. Traders place a rough diamond inside the device, and it tells them what color the rough will yield after cutting — thereby removing the guessing game and letting diamantaires know in advance whether they will get value out of their purchase.

The great synthetics detective

Yehuda himself, though, believes his Sherlock Holmes synthetic-diamond detector is his most influential contribution. The device identified 100% of all lab-grown diamonds in the Diamond Producers Association’s Project Assure test, and it displayed complete accuracy in labeling all but 2.5% of mined stones

as natural.

The idea for the Sherlock Holmes dates back to the 1960s, when Yehuda decided to try and manufacture a diamond. He managed to make diamond dust, but while he never pursued it further, he knew there would come a time when someone would.

“Since I was young, I recall him saying, ‘One day, there will be lab-grown diamonds,’” Dror recalls. “He knew from back then that if someone were to eventually make a lab-grown diamond, there would be a need for a machine that could differentiate between those and natural.”

All in all, it took Yehuda two shots and a few months — mostly spent sourcing parts — to devise a working prototype for the synthetics detector.

While Yehuda never went to university and got terrible grades at night school, he sees ideas in his head, he says, and instinctively knows how to fulfill them. His biggest asset is his deep-set conviction that his ideas will work.

When initially testing the prototype for the Sherlock Holmes, Dror inserted a natural sample that showed positive as lab-grown. He told his father the machine didn’t work. The next day, his father told him it did. Dror tested the sample again, and again it showed up as lab-grown; again, he reported that the device didn’t work. This happened several times over the next three months, with Yehuda insisting each time that the machine was functioning properly. Dror finally decided to test a new sample. Lo and behold, the machine analyzed it correctly, leading him to realize his initial sample had been irregular and had caused a false positive. When he told his father the machine worked, Yehuda’s response was a simple “I know.”

Doing what he loves

Yehuda worries about the future of the diamond industry, which he says is under siege from a lack of marketing, the emergence of synthetics, and a generation that fears blood diamonds and is steering away from mined stones. Yet he continues because he loves what he does. Working with diamonds is all he’s ever wanted to do since that first taste he got as a young boy, and he’s passionate about contributing to the trade’s progress.

The way Dror describes it, Yehuda’s name is synonymous with the diamond sector. “My father has made such an impact on the industry, I tell people, ‘If you don’t know my father, you aren’t in the industry.’”

While Yehuda has no plans to retire just yet, he also has no projects currently on the horizon. “People approach us all the time and say, ‘We want you to do this’ or ‘We want you to do that,’ but right now, we’re just working on improving,” he says. “We need to leave something for other people to do.”

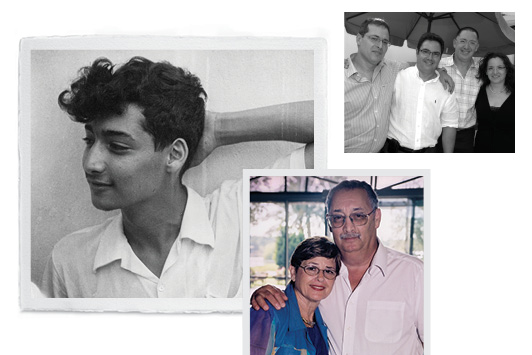

Image: Zvi YehudaArticle from the Rapaport Magazine - November 2019. To subscribe click here.