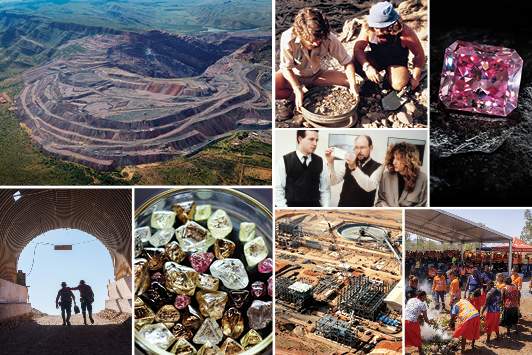

For nearly four decades, Rio Tinto’s Argyle mine in Australia has been an industry stalwart. Not only has it delivered a record 865 million carats of rough over the course of its lifetime, it has been the most steady provider of colored diamonds to the trade, including chocolate browns, cognac, champagne, and of course, the deep pinks and reds for which it’s most famous.

In fact, the Argyle name is recognizable even to those outside the diamond trading business, according to industry experts — a feat few mines have achieved since India’s Golconda projects shut down in the late 19th century. The provenance of an Argyle stone is sufficient to make both dealers and consumers take notice.

“As cheesy as it sounds, there is a certain romance to them, and to colored diamonds in general, because it’s not everyone’s first diamond, just like with luxury watches,” says Harsh Maheshwari, executive director at colored-diamond trading house Kunming Diamonds. “Not everyone jumps into the Patek Philippes or the Audemars Piguets right away; they might first dip their feet in the Rolexes.”

Many colored-diamond dealers share that sentiment. They see the allure of Argyle pinks as a small but central part of their business.

“I started dealing Argyle pinks in my 20s, about 30 years ago, and when I think of all the amazing people I’ve met — from film stars to rock stars and everyone in between — it’s all because of pink diamonds,” says John Calleija, owner and designer at Australian-based Calleija Jewellers. One such celebrity was opera star Luciano Pavarotti, who took one look at the deep raspberry-toned diamonds and fell in love, Calleija recounts. “It was the pink diamond that opened that door and many, many others like it.”

In total, just over 1 million carats of pink diamonds have emerged from the deposit, accounting for more than 90% of the world’s pink supply, Rio Tinto notes. But November 3 marked the end of production at the site. Now that the mine is taking its final bow, where does that leave the colored-diamond industry?

A feeling of loss

“Argyle has been a part of our history for so long that for me, along with the other people who worked here, it’s hard to imagine life without it,” says Patrick Coppens, general manager of sales and marketing for Rio Tinto Diamonds.

Coppens recalls his amazement the first time the famous Argyle pinks were found in the mine. “I remember wondering if it was actually a diamond, because no one had ever seen anything like them before, with that intensity of color,” he relates. “They made their mark on the industry, and there will never be another mine to replace what Argyle gave. It’s going to leave a big hole.”

It’s not just those who worked at the mine who will feel bereft. So will all those who came into contact with the exquisite colored diamonds.

“For somebody like me, who’s been relying on this amazing mine for the last 37 years...we’ll be very saddened by the loss,” says Calleija. “Yes, it’s been great for business, but the loss is more sentimental and emotional, to be honest, like we are losing something really special and beautiful that seemed to have its own personality and character.”

Leibish Polnauer, founder of fancy-colored diamond business Leibish & Co., agrees. He has participated in every single Argyle tender since the mine came into existence.

“It’s going to be missed, but the basic impact on the industry will be more emotional than financial,” he affirms. “Argyle stones have a unique beauty, and it’s painful, like when your dog dies. But people can recover from any pain.”

In fact, Argyle stones set the stage for all other pinks that came after them, according to Scott West, executive vice president of colored-diamond wholesaler L.J. West, citing Isaac Newton’s famous quote about standing on the shoulders of giants.

“People recognize how special the Alrosa Spirit of the Rose stone is, because Argyle was there before,” he observes, referring to the 14.83-carat pink diamond that sold for $26.6 million last month at Sotheby’s Geneva. “And once that ceases to exist, we’ll really feel that reality.”

Looking elsewhere

Perhaps surprisingly, most experts believe the mine’s closing will leave the trade none the worse for wear.

“It will not have any negative impact on the business,” asserts Alan Bronstein, president of the Natural Color Diamond Association (NCDIA). While Argyle pink diamonds are a prominent part of the wider desire for natural colored diamonds, they aren’t a particularly large part, he elaborates.“The closing of the mine reduces the options available for collectors of very, very special pink diamonds, in all their flavors. I like to say that word, because you can have vanilla bean ice cream, and you can have Häagen-Dazs vanilla. They also have Ben & Jerry’s vanilla, and others. Each vanilla tastes a little different, but they’re all still vanilla. When Argyle stones are no longer available, people will begin to look for other options.”

Maheshwari agrees, noting that pinks are available from other sources such as Africa, Brazil and Russia. While the quantity and color of those will never match Argyle’s, he says, people will make do with what’s in the market. “That’s just how the colored-diamond business works. Some years, you have more blues than usual, or some more large pinks than usual. You’ve just got to keep going with what nature provides you with.”

Polnauer points out that there has never been a vast supply of Argyle pinks, and yet the industry has never ceased to thrive. “[The loss] will be painful, but we will heal. The world is not coming to an end, and the industry will not collapse. Other stones will take their place, and while they won’t necessarily be replacements, they will provide alternatives. There is an old European Jewish saying: ‘When there are no Jewish girls at the dance, the Jewish boys dance with the gentiles.’”

He believes the move to other items will be relatively easy, given the premium that Argyle goods will fetch in the next few years. “The prices are already top of the line, and when the prices go up to a critical level, people move on to other goods,” he says, adding that for the price of a 10-point Argyle, people will be able to buy a 3-carat Burmese ruby or a 1.50-carat non-Argyle pink.

A time to stock up

Experts believe the market for Argyle’s colored diamonds will remain reasonably stable for the next two years, given that Rio Tinto plans to hold a pink tender before the end of this year, and a final tender for the last of the ore sometime in 2021.

“I think the market will readjust in the next couple years,” says Polnauer. “Two years down the road, people will start to use alternate things.”

In the meantime, Polnauer has been stocking up on whatever he can get to last him through the initial period after shutdown. He says he’s had a 30% increase in clients looking to buy Argyle pinks over the last six months in preparation for the mine closure.

“We decided to buy as much as we can [in these last two tenders],” he states. “The tenders will be hot potatoes, that much is for sure!”

Calleija, too, believes there will be more buyers than usual vying for the relatively few remaining Argyle pinks to emerge from the mine. “There’s a tender coming up in December, and we’re going to try and get as many [pink diamonds] as we can,” he says. “Those tenders will likely be hotly contested.”

Maheshwari will be looking to build up his collection as well, despite already holding a reasonably robust portfolio. “We’ve been maintaining a healthy inventory and holding on to the most coveted stones,” he says. “So it kind of worked out for us that we have quite a bit of stock.”

Eventually, though, even the biggest inventories will begin to dwindle without new stock to feed on. While the industry won’t feel it in the near term, the closure will definitely have long-term repercussions for the solid Argyle trade that colored-diamond dealers have come to count on.

“We’ve got one of the biggest inventories of Argyle pinks in the world,” says West. “But we’ll have more and more holes. So will everybody else, until it becomes impossible to find a 50-point, SI vivid pink.”

Rising prices

Most colored-diamond traders equate the Argyle situation with the way a famous artist’s last paintings rise in value right before his or her death.

“Prices jump,” says Maheshwari. “I don’t see the prices jumping exponentially in the short term, but within a couple of years, it will start to phase into higher and higher prices.”

West concurs. “It’s continued to go up for four decades now. It probably won’t be linear, and certain years will be stronger than others, but there’s every reason for us to believe it will only increase in value.”

Polnauer, too, believes that “prices will go up forever as the stones become less and less available. The price has already gone up 500% since 2000. If I can make a prediction for the next 20 years, they will go up another 500%.”

Replacing the irreplaceable

Since no other mine currently in operation produces diamonds with Argyle’s consistency or range of colors, where will traders of these stones source product once the final tender is complete?

Argyle never produced pink diamonds over 4 carats anyway, and those in larger sizes were quite rare, says Calleija, so dealers are already used to sourcing larger pinks from other areas. Mining giant Alrosa has found quite a few in its Russian mines, and traders have acquired a semi-regular stream from Brazil and South Africa as well.

There is also the slight chance that a supply of pink diamonds will emerge in the next few years from some of the newer mines. At least, that’s what many in the colored-diamond business hope.

Rio Tinto’s Coppens believes finding another Argyle would provide immense benefit to the trade. “I think the diamond industry needs things like Argyle, to add some color,” he says.

However, the Fancy Color Research Foundation (FCRF) also sees previously purchased Argyle goods as a consistent future supplier. “Looking at underground rough-diamond deposits, we realize that the secondhand market, relatively speaking, is in fact the largest available ‘mine,’” the organization observes. “This new ‘mine’ could become the only significant source for future fancy-color trading.”

Such goods will likely become available as prices rise and stone holders seek to make a quick profit.

“There are diamonds from other mines around the world, which we would love to acquire and use,” says Calleija. “We will also definitely source Argyle pink diamonds from clients that we’ve sold to over the years, because some of them will want to sell, seeing as prices have gone up since they bought.”

Indeed, Maheshwari thinks goods that have been “around” will keep the market going for some time. “There are a good amount of Argyle pinks within the trade, even post-mine life,” he notes. “So I think there will be a lot more business happening within the secondary markets, at least for the next five-plus years, and even beyond that.”

Restoring the land

Long after Argyle’s era in the spotlight is over, workers at owner Rio Tinto will still be involved with the site. The miner has a commitment to the indigenous landowners to restore and regenerate the area. That includes sealing the physical hole, even as the industry deals with the metaphorical one its loss will cause.

The plan involves five years of active work to decommission, reshape and rehabilitate the land, says Chris Richards, general manager of closure readiness at Rio Tinto, and then another five years of monitoring to make sure everything moves along as expected. How the final site will look has yet to be determined and will depend on the feedback the miner receives from site regulators. One possible use is as a tourist attraction, Rio Tinto notes.

However, regenerating the land and preserving the original ecological and cultural heritage is one of the company’s main goals, declares Richards.

The end of the road

Moving forward, the closure of Argyle will “raise awareness of all the other options that are available for people to seek out as their special stone,” Bronstein believes. “Because every natural-color diamond has got a different personality, and you’ve got to meet it before you say, ‘I don’t like that color,’ or, ‘I don’t like that shape.’ So I think the end of Argyle will open up more opportunities for people to ‘date’ other diamonds, because they each have their own personalities, and that’s what you’re looking for in a companion for a lifetime as a piece of jewelry.”

West also has faith that the diamond industry will find ways to forge ahead. “Nothing is going to be exactly like Argyle,” he says. “But there are other opportunities out there, and as entrepreneurs, we will find them, I believe. And I, for one, am going to choose to be happy Argyle was here in the first place, rather than sad that it’s gone.”

Images: Rio Tinto; LeibishArticle from the Rapaport Magazine - December 2020. To subscribe click here.