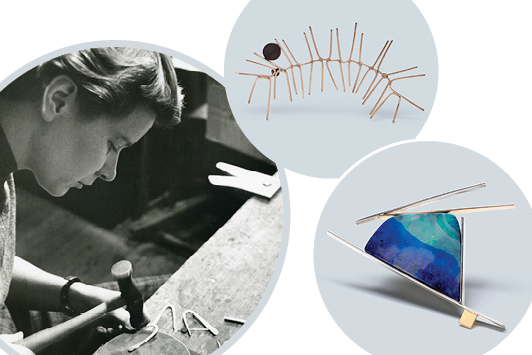

Betty Cooke has been turning the simplicity of geometric shapes into distinctive designs for the last 73 years.

“When I taught, we used to study what can be done with one straight line. I can spend years with a circle. If you have the ideas and the materials, the results are limitless,” says Cooke, who is still designing jewelry at the age of 96.

Known for her artfully architectural, clean-lined modernist style, Cooke first started selling her jewelry in 1947 from her Tyson Street studio in Baltimore, Maryland. In 1965, she and her late husband William Steinmetz relocated her retail space to the suburban Village of Cross Keys neighborhood, establishing The Store Ltd. There, she paired her jewelry with works of international design and folk art, including fabrics from Finnish company Marimekko, furniture by Danish designer Hans Wegner, paper lamps by sculptor Isamu Noguchi, and chairs by designer Harry Bertoia.

In about 2006, Jeannine Falino — an independent curator who specializes in design and craft — met Cooke while curating a mid-century exhibition at New York’s Museum of Arts and Design. Several years later, Cooke asked Falino for help in placing her personal collection of jewelry in museums, which led to an invitation in 2019 to hold a retrospective exhibition at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore the following year. The museum leadership felt this was especially timely: 2020 had been dubbed the Year of the Woman, since it marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th amendment’s ratification.

The aptly named “Betty Cooke: The Circle and the Line” exhibition will include over 160 of the modernist jeweler’s creations. While it was originally supposed to open this fall, it has been rescheduled for September 2021 due to the pandemic. Nonetheless, this fall will see the Walters put out a slate of digital content related to the exhibition.

An elemental aesthetic

The show represents the first scholarly investigation of the jewelry Cooke has designed during her long and distinguished career, notes Falino, who serves as the exhibition’s guest curator.

“Betty has not had a true retrospective, which is surprising, since she is a major icon in the world of contemporary jewelry,” Falino comments. “If not for the pandemic, she would have worked every day at The Store Ltd. She works six days of the week and is fully engaged in all aspects of the business besides the jewelry.”

While Cooke did participate in early national exhibitions and undoubtedly knew the work of other jewelry designers — such as Margaret De Patta, one of the great jewelers of the mid-century — Falino points to other influences in the development of Cooke’s artistic approach: “I think Betty’s aesthetic was far more influenced by industrial or interior designers such as Ray Eames, Harry Bertoia, Isamu Noguchi and Hans Wegner. And that might explain why her work is so absolutely elemental in terms of its shapes. She wasn’t looking over her shoulder at any other jewelers.”

Her work, continues Falino, is “pure form, like objects in space. Not large or bulky, most of her pieces are very slender and almost ethereal. They have a dynamism and trajectory that is very exciting and also very easily worn. They’re made for modern life; they’re not pretentious.”

Mixed materials

In keeping with the studio artists of the 1950s who didn’t care about gold or stones but investigated other materials, “Betty experimented with wood and plastics and pebbles and whatever came her way,” says the curator. “Sharing with mid-century jewelers an interest in minimalism, she was, perhaps, the most minimal of them all.”

While Cooke continued to design in silver, Falino says, “she shifted in the 1960s to 14-karat gold and gemstones. In the past, she had executed commissions for clients who brought her their own precious stones, but in the ’60s and ’70s and onward, she began to actively think about those materials. She tended to gravitate toward really rich, deep colors like fire opals, amethysts or peridot, really bright, eye-catching hues. She also included diamonds and high-quality pearls.”

However, Cooke also combined these precious materials with other, more unusual materials.

“It’s typical of her,” explains Falino, “that a gold bracelet created in 1981 features a beautiful smoothed pebble along with a diamond. It speaks to her ambivalence about using precious materials in the sense that her aesthetic is not about preciousness, but how design and color interact. One fabulous example of this approach is an angular, colorful brooch from 2011 that features a brilliant opal.”

Starting in the late 1970s, Cooke began creating tubular designs, a form with which she became closely associated, according to Falino. “She found that she could purchase very slender tubes made of silver or gold, just big enough to run a thread through, that she could cut into different lengths to create an interesting necklace.”

Longer tubes could be wrapped or twisted into strands around the neck, creating dynamic angles. “Those necklaces became a trademark for her, and a lot of people who love Betty Cooke jewelry consider tubular necklaces their basic go-to piece.”

Playfulness and movement

The jewelry in the exhibition represents classic Cooke creations. “She often conceives of objects from a sculptural perspective,” says Falino. “There is a wonderful ring composed of discs arrayed in all different directions to create volume.”

One piece Falino feels has star quality is a gold necklace with flat discs that are “arrayed edge to edge, but linked in a wave-like design interspersed with vertical elements. The result is both playful and elegant.” It’s also on the cover of the catalog.

Like the tubular necklaces, a small pin from early in Cooke’s career — in the 1950s — shows the interest Cooke had in jewelry that moves with the body. “This kinetic pin is a small square with four silver rods attached to it that swing as you move,” points out Falino.

Cooke also has a longstanding love of nature, says the curator, “and she has produced lots of lively bird and animal pins drawn from her observations of shore birds and the like. One dating from the 1960s is an abstract form made of silver and wood, but I think it looks like a little caterpillar. It shows her interest in playfulness and movement.”

Cooke formed relationships with her clients, creating many custom pieces over the years. One series was commissioned by suburban developer Jim Rouse for his wife Patty as presents for their anniversaries and her birthdays, Falino relates. “They’re meant to contain private messages that other people don’t necessarily see when they look at the jewelry. It’s an intimate message. An example to be shown in the exhibit is one of Betty’s favorites: It’s the number 65 rendered in an extremely abstract way. It’s gold and accented with a small emerald.”

The theme that permeates all of Cooke’s work, says Falino, is the power of the imagination and

the strength of her work ethic. “Years ago, Betty spoke about her creative philosophy, and I particularly love this quote: ‘I can’t wait to come

up with something that I’ve never done before.

And it will be mine.’”

thewalters.org

Article from the Rapaport Magazine - August 2020. To subscribe click here.