From acrostic jewelry to watches, alloys to zinc, ancient Egyptian handwork to modern studio designs, a beautifully illustrated new book provides a glossary of the methods and materials used in producing jewelry.

With

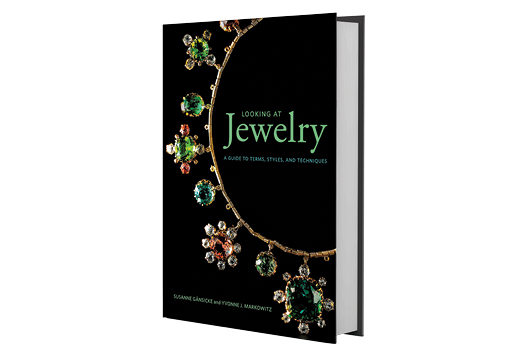

Looking at Jewelry: A Guide to Terms, Styles, and Techniques (Getty Publications), authors Susanne Gänsicke and Yvonne J. Markowitz aimed to create an asset for industry professionals, as well as aficionados reading auction catalogs and wondering what terms like “granulation” meant.

Each of the authors brought her specific expertise to writing and researching the book. Markowitz — the Rita J. Kaplan and Susan B. Kaplan curator emerita of jewelry at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston — addressed forms and styles, while Gänsicke — a trained goldsmith and the head of antiquities conservation at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, California — dealt with processes and materials.

The goal, Markowitz says, “was accuracy,” and the pair made sure the finished volume contained the most relevant terms.

Technological evolution

Creative artists are eager to experiment with new materials and processes, notes Markowitz, and whenever a technology enters a culture, there is an evolutionary process

that occurs.

“For instance, glassmaking first came into use in ancient Egypt during the New Kingdom, about 1550 [BCE],” she recounts. “Today, it’s often seen as an inexpensive material. But when it first appeared in Egypt, as with many technologies when introduced, it was considered extremely valuable and exclusive. In fact, what appear to be lapis lazuli inlays in the incredible mask of Tutankhamen are actually blue glass used in lieu of the prized stone.”

New materials generally start off valuable because of how difficult they are to acquire and work with at first, she explains. “But once the process of how to use the technique is understood, as with glass, the material becomes easier to obtain, and its luster wears off.”

Regardless, these innovations spur progress. “The fact that you can do different things with the new technology or material than you could the old ways, helps advance new forms,” Markowitz says.

Cultural imperative

“There is so much about jewelry that is culturally significant — the metal, the stone,” says Gänsicke. “Materials like amulets or birthstones took on specific values as well as protective qualities.”

Indeed, notes Markowitz, because of jewelry’s meaning in some cultures, “the technologies used to create the jewelry become integral [to that meaning].”

The spread of techniques from culture to culture has been going on since antiquity, according to Gänsicke. “People had a lot of contact through trade, even in the second millennium [BCE]. Although Egyptian jewelry was different from Sumerian jewelry, the materials available were similar, so similar solutions were found.”

That said, she continues, “there were some regional techniques that didn’t travel. In South America, a metalwork process was developed using heated copper and gold alloys and adding acid to deplete the non-precious metals and enrich the gold on the surface of an object. In essence, they were using chemical techniques that the rest of the world hadn’t yet discovered.”

Sharing these cultural influences is part of

Looking at Jewelry’s aim. The book, says Gänsicke, “helps people become aware of the continuity of how jewelry was made, from antiquity until now, and how there is a universal through-line across cultures and millennia.”

Image: J. Paul Getty MuseumArticle from the Rapaport Magazine - June 2019. To subscribe click here.