|

|

Rough Market Faces Its Toughest Year Yet

Insights

Apr 28, 2020 7:00 AM

By Avi Krawitz

|

|

|

RAPAPORT... As the diamond market considers its options during the industry-wide lockdown, manufacturers in India are planning a freeze on rough imports. The move has precedent. Back in 2008, as financial markets collapsed, India imposed a one-month moratorium on rough buying. Ultimately, it helped the local trade realign inventory and gain market share while other manufacturing and trading centers tried to continue with business as usual.

In a letter signed by various Indian trade bodies, the Gem & Jewellery Export Promotion Council (GJEPC) has called on all members to curtail rough imports for at least 30 days beginning on May 15. That would send a message to the banks that the industry was being careful not to raise its debt levels, and would also ease the financial strain placed on companies.

All of this would lead to a “faster restoration of normalcy,” the letter read. With no rough coming in, manufacturers can focus on depleting existing inflated polished inventory, particularly since demand from China and Hong Kong is slowly starting to resurface. In the meantime, they are hoping to resume some polishing activity; manufacturers have a sufficient buildup of rough that they bought from December through March to fuel their factories.

1Q volatility

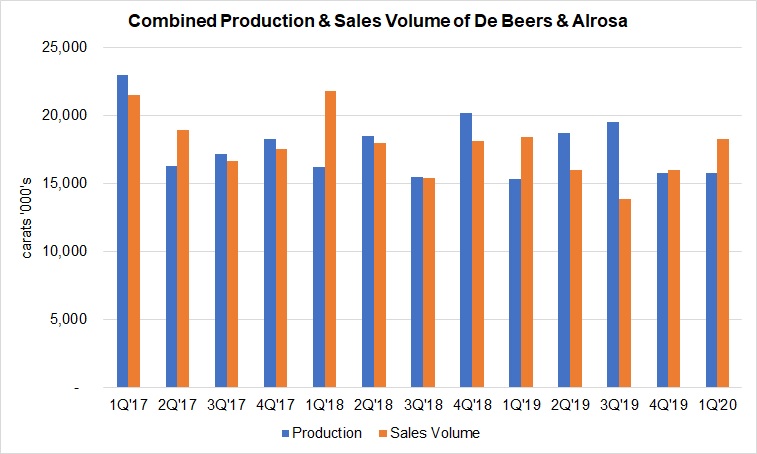

In fact, rough buying was fairly strong in the first quarter. Both Alrosa and De Beers sold more carats than they produced (see graph), enabling them to reduce the significant inventory they had built up in 2019. Although Alrosa’s sales volume fell 11%, it still amounted to 9.4 million carats, while production declined 9% to 8 million carats. De Beers’ sales volume grew 19% to 8.9 million carats, and production slid 1% to 7.75 million carats.

That, of course, was before the coronavirus spread globally, cutting off the trade’s renewed confidence just as demand was starting to pick up after a tough 2019. Indeed, the current crisis is all the more devastating for having hit the industry at a time when it was dealing with a challenging market environment anyway.

Based on reports by Alrosa and De Beers.

2019 report card

Last year, consumer demand in China slowed amid trade tensions with the US and political protests in Hong Kong. Manufacturers struggled to deplete the oversupply of polished in the market, and rough demand was weak due to that bottleneck in polished supply.

That all hit the mining sector hard. Rough prices, revenue and profits slumped during the year.

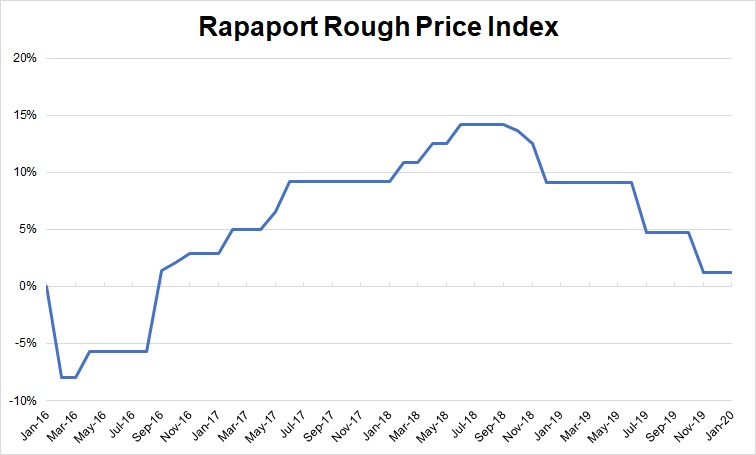

De Beers’ rough price index — which measures price changes for goods on a like-for-like basis — fell 6% during the year, but the company also noted a shift to a lower-value mix of diamonds. This brought its average price down by 20% to $137 per carat. Similarly, Alrosa saw a 6% decline in its index, with the average price of its sales dropping 17% to $98 per carat.

Price levels ended the year slightly above those from five years ago (see graph), following steep increases between 2016 and 2018. Manufacturers bought a lot of rough during that period, leading to the rise in polished inventory.

The Covid response

The miners are now caught in a quandary, trying to assess the market’s future requirements while almost everything is closed.

The mining sector shut down in March and April, along with US and European retail and the dealer and manufacturing segments. Mines in Botswana, South Africa and Lesotho temporarily closed or drastically reduced activity as the respective governments implemented a month-long lockdown. Sites elsewhere were placed on care and maintenance due to the depressed market, including Renard and Ekati in Canada, Liqhobong in Lesotho, and the Williamson mine in Tanzania; it is uncertain when they’ll be able to reopen.

The lockdown and resulting slump in demand will have a dramatic impact on global rough production and supply in both the short and long term, analysts have told Rapaport.

Some companies may not survive once their mines prove financially unfeasible at lower rough-price levels — particularly those businesses carrying high debt, as many are. A select few of the mines will emerge as potential acquisition targets, while others will remain on care and maintenance indefinitely, the analysts predict. Ultimately, the majors will likely gain market share in the rough-selling space.

Alrosa and Rio Tinto continued to operate with social distancing and additional hygiene measures in place, even managing to maintain their production guidance for the full year. Both companies were planning lower production than last year in any case. De Beers, meanwhile, reduced its 2020 guidance by 7 million carats and is now projecting output of between 25 million and 27 million carats.

Miners in quarantine

The market crisis has amplified the challenges that many of the junior and mid-tier miners were already facing in 2019. Mounting debt forced Stornoway Diamond Corp., owner of Renard, to file for creditor protection in September of last year. Firestone Diamonds, which operates Liqhobong, said in October it was assessing its ability to remain operational, given its debt levels and the softening of prices. Petra Diamonds’ debt increased to $596.4 million at the end of December, with weak market conditions hampering its efforts to cut costs and reduce that number.

As for Dominion Diamond Mines — owner of Ekati and 40% of Diavik — Fitch Ratings downgraded the company in April. “The current high-yield debt market may not be receptive to a refinancing,” the credit-ratings agency stated, adding that “it may be difficult to secure a financing alternative, although it remains a possibility. Fitch believes the coronavirus pandemic creates further difficulty in securing financing in the near term.”

Dominion announced shortly after that it was filing for insolvency protection.

“Sorting houses and diamond markets are closed,” Dominion explained. “These are key channels to facilitate the sale of the company’s inventory, so currently there is no ability to generate sufficient revenue to support Dominion’s ongoing financial obligations.”

Other mid-tier miners face similar challenges. The weak balance sheets of Dominion, Petra, Firestone and Stornoway make them particularly vulnerable in the coronavirus crisis, analysts agree.

“Some of these mines should never have been built, and it’s questionable if they will reopen in the near future,” says industry consultant Patrick Evans, a former CEO of both Mountain Province and Dominion. Analysts Kieron Hodgson of Panmure Gordon and Ben Davis of Liberum express similar

sentiments.

Surviving debt

The analysts foresee the mining sector looking quite different post-coronavirus than it did at the beginning of 2020, even if they differ on how it will evolve.

All of them agree that Petra Diamonds has the strongest portfolio among those vulnerable companies, with Hodgson calling the Finsch and Cullinan mines “truly world-class assets” that any miner would want to own. However, the analysts question whether the company can maintain its debt payments in this depressed market environment. Petra said in March that it was considering all “strategic options,” and it has retained the services of Rothschild & Co. and Ashurst as its financial and legal advisers respectively.

Evans and Davis point to Rio Tinto as a potential candidate for acquiring or investing in the Petra mines, since the conglomerate has expressed a desire to stay in diamonds even as its Argyle and Diavik deposits near their end. Rio Tinto has experience in block mining, which is the method in use at Finsch and Cullinan, and has the balance sheet to do it, Evans notes.

As for Renard, Ekati, Williamson and Liqhobong, it’s more likely they will stay on extended care and maintenance rather than shutting down definitively, as the latter option would bring significant reclamation and closure costs, he adds.

Berenberg analyst Richard Hatch expects the companies to emerge from the crisis and return to supply after restructuring their debt, with the possible exception of Stornoway. After all, he says, these assets do generate decent cash flow.

Price over volume

For now, companies are bracing for a dramatic drop in sales and prices in 2020, as rough sales have been canceled for March and April, and there is little to no trading. Petra and Gem Diamonds held sales under a “flexible” structure, which resulted in prices that were respectively 27% and 18% below previous levels.

Alrosa, meanwhile, saw its price index fall just 1.9% in the first quarter, even though it held a relatively small sale in March when the market was already depressed. Hatch believes the company is likely deploying a price-over-volume strategy — that is, electing to avoid selling goods in this weak market and to use its balance sheet to weather the storm, rather than selling its goods at lower prices just to create cash flow.

Alrosa, De Beers and Rio Tinto have strong enough balance sheets to accomplish such a strategy — which is fortunate for them, since the lockdown prevents them from holding any further sales at the moment. De Beers canceled its April sight in Botswana for that reason, preventing any speculation about its price levels.

When rough sales do resume, miners will have to consider curbing supply or significantly reducing prices — or more likely, both. Rough buying is expected to remain low through at least the second quarter as India freezes imports and the manufacturing sector faces tight liquidity and profit margins.

Outlook 2020

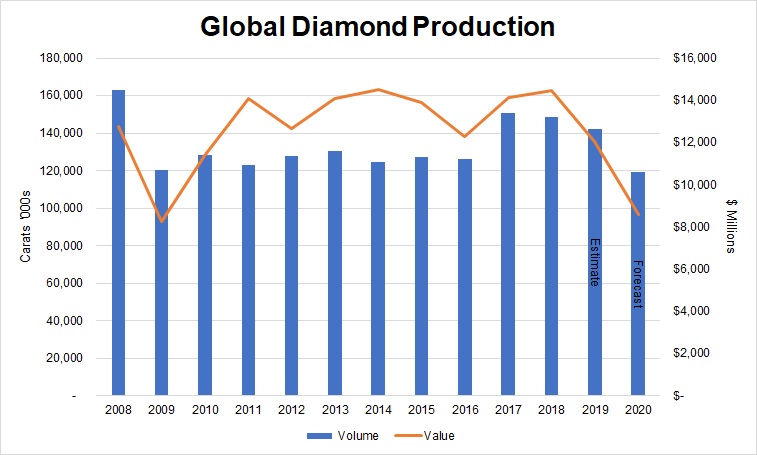

Global rough production will therefore be significantly lower in 2020. Consider that Ekati, Renard, Williamson and Liqhobong — which accounted for a combined 9.3 million carats in 2019 — are expected to remain shut for the rest of the year. There’s also the reduced mine plan at Rio Tinto as Argyle reaches its end of life, Alrosa’s expectations of lower output, and the production lost during the lockdown, most notably at De Beers.

This combination of factors means global production will go down by approximately 23 million carats this year for a total of about 119 million carats, according to Rapaport estimates. At the same time, Hatch projects that prices will drop by about 15%. Based on that assumption, Rapaport expects global rough production value to drop some 29% to around $8.6 billion this year, which would be its lowest level since 2009 (see graph).

Based on Kimberley Process data and Rapaport estimates.

Long-term Shortages

Buffering this drop in production will be the leftover inventory in the mining sector from 2019. Alrosa held a reported 21.1 million carats on March 31, and De Beers parent company Anglo American said it had $500 million worth of inventory as of December 31, with diamonds accounting for the bulk of it.

The miners probably have a sufficient stockpile to sustain the market through 2021, Evans estimates. Shortages are therefore unlikely in the near term, especially considering it will be some time before consumer demand returns to pre-COVID-19 levels.

However, shortfalls may emerge further down the line as consumer demand revives and global production settles at lower levels. Some of the mines may extend their care-and-maintenance status beyond the crisis, and a slew of operations were scheduled to shut down in the next five to 10 years anyway – Argyle, the largest mine by carat volume, among them. No new mines of significance are under development, and analysts suggest the current crisis may delay expansion projects to extend the life of some existing operations.

Evans sees some opportunity for lab-grown stones to compensate for any shortages in the natural-diamond market, particularly in the lower-value, Argyle-type supply. He also cites recycled polished as another growing area of supply.

Whether long-term shortages will translate to a recovery in rough prices ultimately depends on the manufacturing sector and the polished market. With the recent decline in polished prices, manufacturers are unlikely to buy rough at unprofitable levels as they have in the past. Certainly, banks will be less inclined to fund such purchases, as they already view the diamond trade as high-risk.

That leaves the mining companies to negotiate their prices to a level that can sustain their highly leveraged operations but also enable a viable trade. Some miners may need to sell at lower prices to generate cash flow; if anything, analysts agree, COVID-19 has exposed the high debt levels of mid-tier miners.

The companies with strong balance sheets and high-volume supply will emerge from this crisis with an even larger share of the mining space — and even for them, it will take time to return to revenue and profit growth, since manufacturers have clearly lost their appetite for rough in 2020. With little known about how consumer demand will emerge from the crisis, the hope is that curbing rough supply will support a recovery.

This article was initially published in the April edition of the Rapaport Research Report. Subscribe here.

Image: Shutterstock

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tags:

Alrosa, Avi Krawitz, Berenberg, De Beers, diamonds, Dominion, Jewelry, Panmure Gordon, Rapaport, Rio Tinto, stornoway

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|