|

|

Crazy, Scarce Rough

Field Notes

Feb 24, 2022 7:55 AM

By Avi Krawitz

|

|

|

The diamond market is in a Mexican standoff, one diamantaire observed with an air of bewilderment in a conversation this week. No one knows who’s going to move first — buyers who have orders but lack urgency or suppliers who are at times unwilling to sell because they expect to get better value in the future, he mulled.

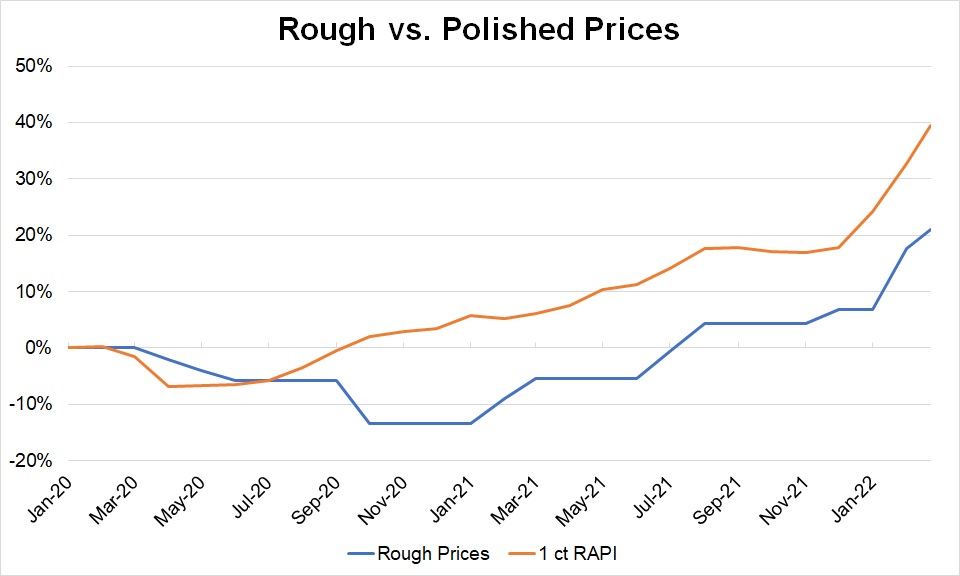

He’s not alone in expressing this sentiment. Many are in a state of confusion as diamond prices have increased by considerable margins in 2022. The RapNet Diamond Index (RAPI™) for 1-carat diamonds is up 12.3% since the beginning of the year, on track to record its strongest growth in over a decade for a quarter in the first three months. Rough prices have also spiked, with De Beers and Alrosa raising prices in January and, unsurprisingly, again at their February sales, which took place this week (see graph).

But who is following whom? Are the mining companies watching the trend in polished to justify their hikes, or are manufacturers raising their prices due to their higher rough costs? Or are retail jewelry sales strong enough that they’re pulling the rest of the supply chain along for the ride?

The answer is none of the above. There is a fourth element exerting influence on the rest of the pipeline: the secondary rough market.

Soaring premiums

In industry lingo, there is primary rough supply from De Beers, Alrosa, and to a lesser extent, Rio Tinto, which sell to customers on a regular basis via long-term contracts. The secondary market consists of rough sold at auctions and goods traded between dealers or sold by those primary buyers (sightholders) to smaller manufacturers or dealers.

Rough prices have skyrocketed on the secondary market in the past few months. Brokers describe “insane” premiums at auctions and in the trade. Categories of De Beers goods have sold at the company’s auctions for 50% to 80% higher than at the sight in January, according to market sources. Goods are also selling at astronomical margins between dealers.

So, while it’s easy to point a finger at the mining companies for hiking prices for the second consecutive month, one can’t blame them for taking their cues from secondary platforms. After all, that’s where prices reflect bids made by the trade, rather than what the miners set.

Trading on expectations

The reason behind the craziness is twofold. An element of speculation has crept into both the polished and rough sectors that is influencing trading, and there are shortages of rough available on the secondary market.

Let us first consider the speculation. Polished suppliers expect prices to continue to rise, since rough costs have increased. But even though jewelry retail remains positive, polished buyers have grown more cautious in February.

Polished demand has tapered off as post-holiday restocking has slowed, and economic and geopolitical factors have injected some uncertainty into the arena. From the polished supply side, inventory levels have gradually increased in the past few months to exceed pre-pandemic levels. A lot of rough was sold in 2021, and those goods have emerged as polished. The grading labs are still seeing seasonally high submissions. So where are the polished shortages?

It seems the scarcities reported in the polished market are because it is difficult to find the right diamond at a profitable rate — or because suppliers will only sell at tomorrow’s prices. Larger manufacturers, which gained strong liquidity during 2020 and 2021, are willing to hold onto inventory with the expectation its value will increase.

That puts polished dealers in a pickle. They’re struggling to buy, because valuations are higher than the price for which they sold the goods they’re trying to replace. That has created a perception of shortages on the polished market, fueling a rush for rough.

Rough changes

However, unlike in the polished, there are scarcities in the rough dealer market that are real — the second reason behind the enormous premiums.

Fundamental changes in the way the rough segment operates are creating shortages in the secondary market. The mining companies are pushing for a quicker, more efficient supply chain to satisfy growing demand while production is waning.

De Beers and Alrosa are doing this by curating supply to their contracted customers according to whether they’re a manufacturer that converts rough to polished, a retail jeweler that relies on rough for self-manufactured in-house supply, or a dealer that profits from supplying rough to the secondary market. The idea is to have rough processed into polished sooner rather than later. The miners are therefore supplying more to cutters and less to dealers that sell their goods on the secondary market.

De Beers is also emphasizing beneficiation, providing more of its production to sightholders with factories in Botswana, Namibia and South Africa. That means that fewer De Beers rough is getting to the traditional centers such as Antwerp, Ramat Gan, Mumbai and Surat.

Inventory sell-off

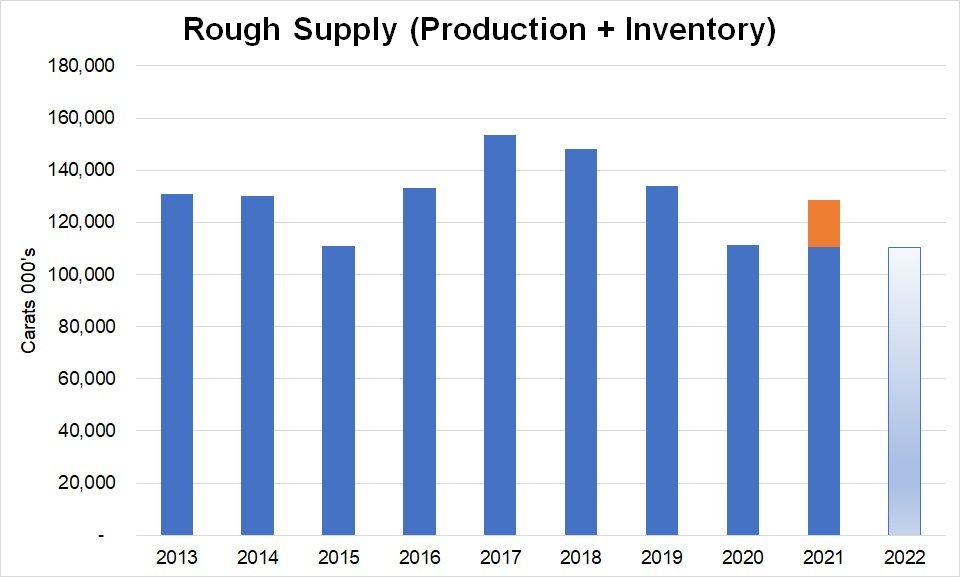

There’s also less rough being recovered. In volume terms, global production was similar to 2020 and will likely remain at those levels in the near term — which are below pre-pandemic ones. The decline in output wasn’t felt in 2021 because the mining companies had inventory left over from the previous year. In 2021, the mining companies depleted the excess stockpiles they built up during the depths of the pandemic shutdowns. So, while production volume was flat for the year, actual supply was closer to 2019 (see graph).

The same won’t occur this year since there is no stock to offload. The major miners are now selling whatever they produce, which is historically low. Their sales growth is being driven by price appreciation rather than volume. Consider that De Beers’ January sales were valued at $660 million, the same as a year earlier. However, the company’s like-for-like average price index grew 11% in 2021, and it raised prices an estimated average of 10% in January. The company sold fewer diamonds for the same value during the month.

It’s therefore understandable that there are shortages on the secondary rough market, pushing up prices there. That’s all playing out now since the change in De Beers’ and Alrosa’s supply policy only recently took effect, and no excess rough inventory is available as a backup.

Of course, good jewelry demand is also a factor. Prices climb when demand rises or supply falls, or both happen, as we are currently experiencing. But those fundamentals aside, there has been a swift change in the rough market that has left the midstream in a spin. It needs to adjust.

Lasting impact

There will be casualties as the pipeline becomes more efficient. Rough dealers are being squeezed out of the market for the reasons outlined above. And polished traders are facing increased competition from manufacturers, which are looking to improve their profit margins by cutting out the middleman and selling directly to jewelers, mainly online.

The other segment affected is that of small manufacturers that rely on dealers for rough supply. The large-scale cutters have access to rough that their smaller colleagues do not, and, after enjoying a windfall in 2021, they have strong liquidity to pay the higher rough prices.

These are long-term changes currently taking effect. But they also reflect a shift in the market’s short-term dynamic.

The main reason 2021 was such a good year for everyone was because demand drove growth. Excellent retail-jewelry sales translated to robust polished trading, which resulted in steady increases in polished prices. That subsequently influenced better rough demand, which justified the rise in rough prices. Remember, the rough market initially trailed polished in its recovery from the Covid-19 shutdowns.

The market found a healthy balance during 2021, but that has changed in 2022. The market is now more influenced by supply than demand, largely because of the dynamic on the secondary market. Rough prices at auctions and among dealers are speculatively high, and unsustainable – even as there is not enough rough available. And just as the rough trade is influencing almost daily increases in the polished while on the up, the rest of the market will likely suffer when the rough bubble bursts.

If the current conditions persist, a correction will only be a matter of time. To return to the bewildered diamantaire’s analogy, in a Mexican standoff the next move typically sees someone shoot or withdraw.

The market is forcing rough dealers to withdraw because shooting will mean paying yet higher prices. They’re struggling to find goods because there is less available and cannot pay such premiums when they find the right rough. There simply is not enough rough available for dealers at the moment.

In its healthiest state, the market should be demand driven – as we experienced last year. Let’s not allow the success of 2021 to fool us into believing the same equilibrium has continued. A lot has changed in less than two months.

Image: Table-top view of De Beers rough. (De Beers)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tags:

Alrosa, Avi Krawitz, De Beers, diamonds, Jewelry, Rapaport

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|