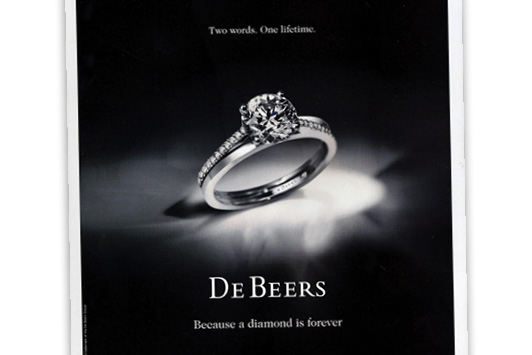

In 1947, Frances Gerety, a copywriter on the De Beers account at N.W. Ayer & Sons in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, created a phrase that has become iconic: “A Diamond Is Forever.” In 1999, Advertising Age named it the Slogan of the Century. Today, it’s a line on the lips of many in the industry — not as a wistful longing for the past, but as a reminder of a successful generic campaign that drove diamond sales.

The consensus among many wholesalers is that there is an immediate need for a high-level, sustained marketing campaign to promote diamonds across the US. However, there are also wholesalers who, though supportive of advertising, question the viability of a generic approach.

Macro vs. Micro

“We are a super-powerful industry, and we have no marketing at all,” laments Ami Sarbagil of diamond manufacturer E.M Trading in Chicago, Illinois. A strong voice for a concerted industry effort, he points to major consumer companies such as Coca Cola and Starbucks, which constantly advertise all over the world even though their products are household names.

“Diamonds have lost their sizzle” is the succinct appraisal from Gaurav Khandelwal (aka “GK”), sales director at Union Gems in Houston, Texas. Khandelwal, whose company specializes in fine-make diamonds, emphasizes the need for a “full spectrum of advertising” that would lift all segments.

“From a demand perspective, diamonds are no longer considered the consummate luxury purchase,” he says. “Travel, designer handbags and electronics increasingly compete for discretionary spending. We’re not creating awareness of the product. In 2015, Apple spent $1.8 billion on advertising; by comparison, the Diamond Producers Association (DPA) budget was $70 million in 2018.”

But David Rakower, president of New York-based manufacturer Joseph Asher Collection, questions the effectiveness of an industry-wide generic marketing campaign. “It doesn’t seem reasonable. I don’t know of any other industry that promotes itself as an industry, unilaterally across the board, except perhaps ‘Got Milk?’” — a 20-year campaign originally created for the California Milk Processor Board that increased milk sales in California but not the rest of the country.

The automobile industry doesn’t promote cars, he points out; Lexus and Ford run their own ads. “Establishing and creating recognition for a specific brand will increase awareness for the entire category. If you pump jewelry-related advertising out into the world, consumers are going to be more inclined to buy jewelry, whether it’s from Tiffany & Co. or their local jeweler.”

For his part, Rakower provides his customers with marketing support through co-op advertising and trunk shows. Sarbagil forwards professional, diamond-focused videos to his clients, but sees this as “just a drop in the bucket.” Khandelwal shares product knowledge with his customers, but doubts this helps generate consumer demand.

“Diamonds represent an idea; they evoke emotion,” says Sarbagil, who advocates reviving “A Diamond Is Forever.” And Khandelwal cites the “wildly successful” De Beers ad for three-stone anniversary rings that, in the words of the ad, symbolized “past, present and future.”

Tone-deaf message?

The goal of any campaign is to convey a message that deeply resonates with the public and is understood instinctively. While Khandelwal commends DPA advertising as a “step in the right direction,” it isn’t the “significant, holistic” campaign he envisions.

And its message may have been buried. The group’s “Real Is Rare, Real Is a Diamond” campaign “falls on deaf ears,” according to Rakower. “It is a response to lab-grown diamonds, but for the most part, consumers are unaware that a conflict exists between lab-grown and mined diamonds. It is definitely not promoting the beauty of giving something special to someone you cherish.”

Current advertising is also missing another critical element, Rakower says: It ignores the concept that diamonds and diamond jewelry are perfectly in tune with today’s more casual lifestyle. “People aren’t getting gussied up to go out on the town like they did in the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s. We have to show that there is nothing wrong with pairing diamond studs with jeans or wearing a diamond bracelet to work. It is imperative that we find a message that is congruent with a younger, more casual demographic, and I don’t mean just millennials.”

But millennials do have to be a focus of the campaign. Neither they nor Generation Z have been exposed to generic diamond advertising, notes Sarbagil. As a result, they haven’t experienced the “feelings of power and confidence” diamond ads once conveyed.

The campaign must also address millennials’ concerns about the industry. “They only hear the bad things,” says Sarbagil, highlighting the need to counter the “blood diamond” narrative and the belief that diamonds harm the environment.

Khandelwal agrees the industry needs to tell a better story. Current advertising, he says, fails to showcase the trade’s positive socioeconomic impact and overlooks the beneficiation programs in diamond-producing and -manufacturing regions.

The practical side

Of course, this level of advertising costs money, and wholesalers have given thought to funding methods they deem fair and uniform.

Sarbagil argues for an import tax that would be earmarked for marketing, along the lines of the 0.01% that the Israel Diamond Institute levies. Another option he suggests is a $200 fee for any import above $200,000. He considers both proposals “affordable” for the trade.

Khandelwal, meanwhile, is looking to rough sales for a solution. “Rough is the most organized part of the pipeline,” he comments. “We could have an across-the-board tax on the sight boxes and tenders. Some rough sold by artisanal miners might slip under the radar, but artisanal miners need the additional proceeds to support their local communities. That would look great for the industry as a whole.”

Who would collect these funds and run the campaign is still a matter of debate, however.

Trade bodies lack the necessary consumer-focused skills and experience to organize an effective advertising operation, argues Khandelwal. For example, the World Federation of Diamond Bourses (WFBD) has knowledge of diamond manufacturing and trading, but that doesn’t necessarily translate to understanding the norms and nuances of the American consumer.

Sarbagil thinks US groups such as the Diamond Dealers Club (DDC) in New York and the Diamond Club West Coast (DCWC) could provide the impetus for an industry campaign, since they are organized and consist of wholesalers and manufacturers — parties that would support the effort.

Even Rakower believes it would be easy to assemble a group of industry leaders who could form a committee and collaborate on a marketing plan. However, he stresses, “we can’t keep waiting for someone else to pick up the reins. If you’re a brand, you have to support the brand. If you’re generic, you have to promote what you can do in a generic way to help your customers sell things.”

Khandelwal echoes this sense of urgency, declaring that the industry is at a turning point. “Continued lack of profitability will lead to an exodus of capital — intellectual and financial — throughout the pipeline,” he says. “I’m not sure if there is a perfect solution, but inaction is unacceptable.”

Image: De BeersArticle from the Rapaport Magazine - January 2020. To subscribe click here.