A cut grade of Excellent from the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) is a target many diamond manufacturers are eager to reach. Recently, some of them have gotten creative in their efforts to achieve that goal — a bit too creative, critics say.

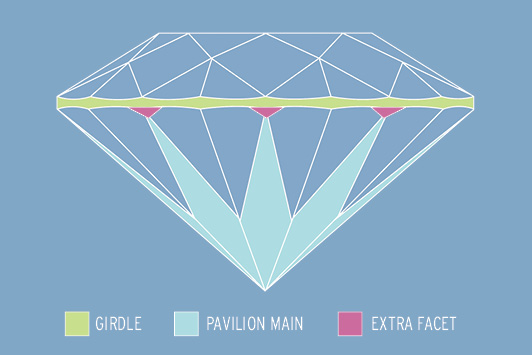

Round brilliants have started turning up with extra facets where the girdle meets the “pavilion main” facet, which runs down to the bottom tip of the diamond. Polishers appear to have made these tiny adjustments to take advantage of the GIA’s method of scoring a stone’s cut quality.

“We began seeing stones with multiple extra facets at the pavilion main/girdle junction earlier in 2019,” says Phil Yantzer, the GIA’s vice president of US laboratory operations. “These extra facets may be able to impact the measured girdle thickness that is used in part to determine the GIA cut grade.”

Depth perception

The GIA calculates a brilliant-cut diamond’s depth by adding together the height of the crown, the average thickness of the girdle and the depth of the pavilion. It expresses this as a percentage of the stone’s diameter, with 63% being the maximum permitted depth for an Excellent cut. A diamond that is too deep reflects light badly and can appear small, while a disproportionately thick girdle can look ugly and squander valuable weight on a part of the stone most people don’t see.

However, the GIA faces a problem when there’s an extra facet at the junction of the girdle and the pavilion. In addition to making the girdle thinner, that small feature reduces the length of the pavilion main, which is the plane the GIA uses to measure pavilion depth, explains Shimon Gerstensang of the Rapaport Group’s trading department.

“This extra facet is not a part of the girdle, is not a part of the crown, and is not a part of the pavilion,” he says.

In other words, the top-to-bottom distance of the extra facets gets “lost” when the GIA calculates the total diamond depth. This creates the possibility that diamonds will get a lower depth percentage than they deserve, potentially inflating their cut grade.

Full disclosure

One of the most vocal critics of this practice is Garry Holloway, a diamond retailer in Melbourne, Australia. A geologist by education, Holloway has long studied diamond cuts and has created an online program for assessing cut quality. The case of the extra facets was the subject of a YouTube video he put out in August, explaining how a stone with 64.9% depth was able to achieve an Excellent grade.

Holloway believes the GIA has a responsibility to alert the public to this phenomenon by publicizing the certificate numbers of the relevant stones and posting a notice on its website. “The GIA should name and shame the companies that produced these cheated-girdle diamonds,” he declares in an interview with

Rapaport Magazine.

Rounding off

For its part, when the GIA became aware of the practice, it began classifying the stones as “round modified brilliant” rather than simply “round brilliant.” This put them out of reach of a cut grade, which the GIA only assigns to the standard shape. In addition, it adjusted its instrumentation to prevent the extra facets from affecting the grade, and invited clients to resubmit stones that had come back as round modified brilliant.

Yantzer won’t speculate on whether

any diamonds with an incorrect cut grade have already reached the market. Asked whether the laboratory should publish a warning, he says there is no way to identify which diamonds may have received an inflated score.

Number-rounding can sometimes be responsible for legitimate mismatches between the “measured” depth that appears on a grading report (the distance from table to culet) and the “calculated” depth the lab uses to determine the cut grade, the GIA adds. As a result, diamonds with a measured depth exceeding 63% can sometimes correctly receive an Excellent cut grade because the calculated depth came out lower, according to Yantzer.

Responsible selling

That said, the fact that there are around 37,000 diamonds on RapNet with a depth ranging from 63.1% to 65% and an Excellent GIA cut grade has prompted some, like Holloway, to voice concern.

Irrespective of what appears on a GIA report, sellers need to show responsibility for what they sell, argues Saville Stern, RapNet’s chief operating officer.

“Diamantaires add value due to their experience and knowledge, and they should not ignore this in the face of a grading report,” he says.

Image: RapaportArticle from the Rapaport Magazine - December 2019. To subscribe click here.