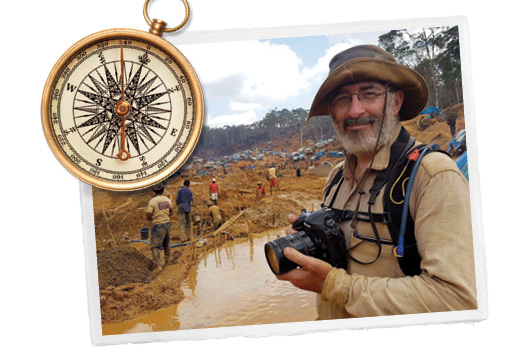

Vincent Pardieu is a man of many talents. He’s embarked on 148 field expeditions to gem deposits in Asia, Africa, Australia and South America. He’s served as senior manager of field gemology at the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) in Bangkok, Thailand; as director of the Asian Institute of Gemological Sciences (AIGS) lab in the same city; and as a gemologist at the Gübelin Gem Lab in Switzerland. On top of that, he’s a writer and documentary producer.

For the past 20 years, he has been traveling to gem deposits globally to help labs build reference collections for determining stones’ origins. His latest collaboration has been with the Bahrain Institute for Pearls & Gemstones (DANAT) and miner Greenland Ruby.

Rapaport Magazine caught up with Pardieu in Bangkok at the recent International Colored Gemstone Association (ICA) Congress, where he gave a talk about “gem paintings” — the art of using non-gem-quality rough stones to create beautiful pictures, which help provide a livelihood for mining communities.

Is it possible to achieve traceability in the colored-gem sector?

Yes and no. Traceability is possible for stones that will be mined tomorrow, coming from a legal mine, but it’s complicated for those mined in the past. Besides being beautiful and rare, gems are durable, so most will survive us. If you are searching for a fine 5-carat Burmese ruby, the probability of sourcing it from a mine today is almost zero. On the other hand, death, divorce, debt and disaster (the four Ds of auction houses) are responsible for regularly bringing back exceptional gems to market. So how do we deal with traceability for recycled gems?

For stones mined nowadays, in some cases it is possible to have traceability [programs like those] offered by Greenland Ruby, a vertically integrated mining company operating in a first-world economy. But a small-scale miner working in a developing nation in Africa or Asia will have to tackle issues of safety, security and corruption. If the mine workers are well dressed, people might think he’s wealthy. He may then be harassed by corrupt officials or jealous neighbors. Corruption and jealously are the biggest hurdles on the journey toward formalization, transparency and traceability. The assassination of [gem expert] Campbell Bridges in Kenya in 2009 is a classic example.

What issues does field gemology face today?

Firstly, finance, as you need to fund your mine visits. Sadly, most labs don’t invest in research as much as they should. Some are too busy printing reports, and others lack both qualified people and income. Second, a field gemologist is rarely home, so this profession is personally challenging. Third, danger: You may at some point get malaria, food poisoning, accidents, etc. You have to expect the unexpected — good or bad.

Is there a future for field gemology?

Yes, because there is demand for origin reports, because technology gets better, and because currently origin determination is being done by [only a] few experienced gemologists providing their opinion on a stone. Given the current age of these experts, when they retire, who will do this? Most young people I meet are not willing to sacrifice their work-life balance like these famous old-timers. I believe the only way origin determination can continue in the long run is via comparison of data from the customer’s stone with data collected from stones from a reliable reference collection. So somebody will need to build that reliable database.

What points should labs consider when building a reference collection?

A reference sample is a sample properly documented with the four [questions] of field gemology: when, where, from whom, and how? When was the sample collected? For example, if it was sourced in 1975, it cannot be from any deposit discovered afterward. Where was it acquired? At the mine? Or at a market? As parcels in markets are often mixed, the probability of contamination is higher. From whom was it collected? Directly from a miner or a dealer? And finally, how? Did the gemologist witness the stone taken out of the ground or not? Answers to these questions will establish the reliability of the reference sample.

What political challenges do mining companies face?

In theory, governments are supposed to help. In practice, whenever I faced problems in the field, it was from someone in uniform trying to extract money. From what I understand [based on discussions] with miners, many had similar experiences. If taxes are high and corruption common, miners keeping a low profile might decide not to declare their production for both safety and financial reasons. Let us remember, stones are easy to smuggle, and people are easy to corrupt. If you have a stone worth $100,000, you can choose to either pay $100 for it to cross the border, or pay $15,000 in tax (if tax is 15% like it was in Zambia in 2019). Sadly, some government officials are more likely to make a few hundred dollars on the side than have the country receive significant income from taxes.

How do you see the impact of mining on local communities?

Mining (legal or not) is excellent, as it provides employment. Besides mining, what are the options for many people in remote areas? Farming? Hunting? Logging? If there is a civil war, they can become fighters, either for the government or insurgents. Given that farming does not often provide work all the time, many people I’ve met in the field consider mining to be a good alternative. The challenge for governments is to make mining legal and to formalize it. The danger is when mining is illegal, as police will not be present, [and] illegal mining villages will offer an excellent refuge for other illicit activities such as poaching, drug dealing, etc. On the other hand, when mining is made legal and accessible, it creates legal jobs. When associated with good governance, it may give rise to an ancillary industry and facilitate infrastructure development. Business opportunities — from supplying the miners to producing gem paintings — can be introduced and supported and might benefit both the miners and the communities in the surrounding area in the medium to long term.

What is your opinion on lab-grown diamonds?

I don’t have a problem with lab-grown stones. When synthetic rubies appeared toward the end of the 19th century, the ruby trade went into shock; many companies went bankrupt. Still, the ruby business survived and recovered by creating labs [for gem-testing]. Gem labs were born thanks to cultured pearls and synthetic rubies. Synthetic diamonds are just a different product. They may impact the industry in the short term; however, in my opinion, people will still prefer to put money on natural gems because there is no resale value for synthetic gemstones.

What new project are you working on now?

As I have said before, in the next 10 to 15 years, I do believe that origin determination will primarily be done via a reliable reference collection. So my focus now is to continue building an authentic, independent gem reference collection that I can make available to labs globally for their research.

Images: Vincent Pardieu; ShutterstockArticle from the Rapaport Magazine - March 2020. To subscribe click here.