Cultural nuances, the discovery of new deposits, and the advent of the machine age have all contributed to the evolution of diamond cutting. Practices have gone from simple polishing in the ancient world to complex faceting that yields exquisite works of art.

The most common style today is the modern brilliant cut; invented in the early 20th century, it follows the principles of the 4Cs — cut, color, clarity and carat weight — and forms the backbone of the wider diamond and jewelry sector. But the niche demand for older cuts is growing, along with the segment of lapidary experts operating in this market.

The vintage appeal

A good example of this is the fourth-generation firm of Bernard Nacht, which recently launched a product called the Crown Jubilee diamond — a trademarked proprietary cut that comes with a report from the Gemological Institute of America (GIA).

“We acquire old mine and old European-cut diamonds that are chipped and abraded from years of wear and have been cut [deep] to maximize weight,” says company president Alan Nacht, describing the recutting process that produces the Crown Jubilee. “We clean the girdle, remove chips, abrasions and any inclusions, which may impact the beauty of the diamond. Our process involves maintaining the original outline of the old diamond and applying our distinctive facet pattern to maximize the gem’s brilliance. In this manner, we can maintain the personality of the material — its history and the poetic allure.”

Sylva Yepremian can affirm the popularity of vintage cuts. The Los Angeles, California-based jewelry designer has over 20 years of experience crafting custom pieces for a discerning pool of clients, who she says “form less than 3% of the market [and] are less interested in anything conventional. For the past 10 years, I can’t keep a pair of old alluvial diamonds in stock. To me, these diamonds are the true Rembrandts of our industry. Clients who appreciate old-mine diamonds have developed a sophisticated eye. They have graduated from their purchases of the Cartier love bracelet [or the Van Cleef & Arpels] Alhambra necklace and no longer want something everybody else can get.”

Many credit estate dealer Fred Leighton with popularizing vintage diamonds and jewelry some 25 years ago. By introducing vintage jewelry to the red carpet via celebrities, Leighton mirrored publicist Dorothy Dignam’s strategy from the ’50s and ’60s, in which she helped raise diamonds’ profile by ensuring their placement among Hollywood stars. In the past 10 to 12 years, auction houses and estate jewelers have contributed to this domino effect by marketing to consumers through social media and other online platforms. Movies and historical dramas on streaming services like Netflix have also led to a resurgence of demand for revival jewelry.

Replicating the look

When crafting vintage-style jewelry, designers need vintage-style diamonds. To cater to this growing niche, contemporary designers are turning to another segment in the diamond processing industry: lapidary artists who execute old-style cuts on new rough.

Yoram Finkelstein of GemConcepts began specializing in this field 20 years ago. “Many will cut a diamond in a vintage style but will use modern standards, which doesn’t work,” he comments. “The result will be a diamond [that] looks like an old mine cushion, but it won’t feel like one.”

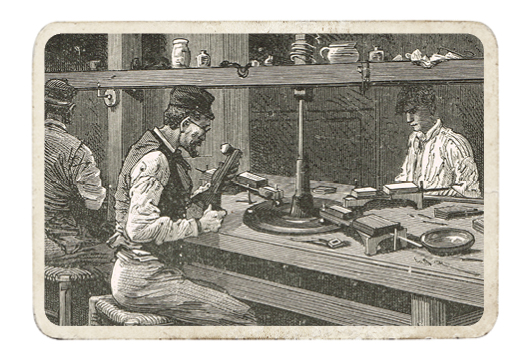

Most cutters are trained to follow these contemporary standards and styles because the primary market is for the modern brilliant cut. They’ll employ advanced techniques, machinery and artificial light. However, “in the old days, diamonds were primarily worn by royalty and courtesans at night when they would attend balls,” Finkelstein points out. “Candles illuminated the festive halls, so a diamond facet required a larger surface area to capture and return the light to the eye or sparkle in that dim lighting environment.”

The value of vintage-style stones has changed with the times as well. Finkelstein recalls that “20 years ago, old diamonds were valued based on an estimation of what their grade would be after they transformed into a modern brilliant-cut gem, which is no longer the case. To share an extreme example, I remember paying $100,000 19 years ago for an approximately 10-carat-plus old diamond of exceptional quality. The same gem today would probably cost me $2 million.”

Diamond cutting allows for a different perspective than other stones. When a lapidary artist is cutting a colored gem like ruby or emerald, the final desired color is what dictates the decisions. With diamonds, the lapidary artist looks toward the sun, working to trap light inside the gem with each facet until the diamond ceases to be a rough stone and becomes a celestial object in its own right.

Image: Historical Images Archive/Alamy Stock PhotoArticle from the Rapaport Magazine - June 2020. To subscribe click here.