Enhancing the stone

Over millions of years, inclusions form naturally within an emerald. Most are visible to the naked eye and can affect the perception and value of the stone. Since these small imperfections exist in about 99% of emeralds, many people seek to reduce their effect.

“Enhancing the beauty of emeralds is not new,” says antique-jewelry specialist Ioannis Alexandris, CEO of Gemolithos. “The practice of filling the fissures with oil dates back to ancient Greece.” In the many antique emerald jewels he sees, “nearly all have been oiled to some degree.” Of course, beauty is in the eye of the beholder, he adds, as inclusions can have interesting patterns — such as the spoke-like lines that characterize trapiche emeralds.

It has become standard practice to treat emeralds with near-colorless to colorless oils, resins or other compounds to fill the fractures and make them less noticeable. This generally intensifies the color as well, since there are fewer apparent flaws to block the passage of light.

Due to its high viscosity, a commonly used filler is cedarwood oil. Other oils include mineral, liquid paraffin, castor, and clove. However, since oils tend to dry out and decompose over time, synthetic liquids and epoxy resins have gained traction.

“Resin filling is more durable, with a longer lifespan, [and] may last for a few years,” says Gagan Choudhary, director of the Gem and Jewellery Export Promotion Council’s (GJEPC) Gem Testing Laboratory (GTL) in Jaipur, India.

Still, he notes, resin is not permanent. In addition, when oil dries out, the stone can be cleaned with alcohol and refilled, but when resin decomposes, cleaning and refilling is tricky and must be done by professionals with specialized equipment, he explains.

There are “challenges involved in the correct identification of filler substances, especially when an emerald goes through multiple steps of filling, cleaning, refilling, or when an emerald is filled with multiple fillers, or when glue is used,” continues Choudhary. GTL confirms the presence of resins and oils by using spectroscopy techniques like micro-FTIR or micro-Raman analysis.

For grading purposes, the level of treatment is generally divided into categories: none, insignificant, minor (F1), moderate (F2) and significant (F3). These levels can impact a gem’s price. All else being equal, an emerald with a minor treatment rating will generally be worth more than one of the same color and clarity with moderate enhancement, which in turn will be worth more than one with significant treatment.

Given the downsides of current treatments, many studies are underway to find better filling options. In Colombia, for example, the industry asked CDTEC GemLab several years ago to find a high-viscosity natural filler that was colorless or near-colorless, stable over time, and easy to remove. After a long process, the lab found what it was looking for, naming the product Naturalys. It has been on the market for a few years now, and time will tell how well it performs in the trade.

Verdant growth

While lab-grown emeralds may garner less media attention than lab-grown diamonds, they are a product category in their own right. As with diamonds, they have virtually the same chemical, physical and optical properties as their natural counterparts. Producers of these stones use one of two processes: the flux method, which became commercially available on a wide scale in the late 1930s, or the hydrothermal method, which started in 1960.

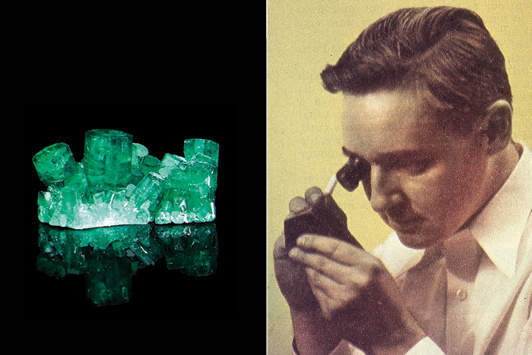

“In 1848, J.J. Ebelman was the first to report success in growing flux synthetic emeralds, but in 1888 and 1890, two published reports by P. Hautefeuille and A. Perrey forged the path for all later flux emerald growth,” says research gemologist Robert Kane.

Then, in 1928, a prodigious 14-year-old in the US named Carroll Chatham began experimenting with these techniques in a homemade lab.

“My father combined the ingredients of emerald — beryllium, silica, alumina and chromium — with a substance that these chemicals would dissolve in, [known as a flux,] at around 1,200 degrees Celsius,” relates Chatham’s son Tom. “He added an emerald seed to this super-saturated solution and heated it to temperatures that caused emerald to crystallize out.”

The younger Chatham recounts that “when my father went off to college at Caltech, he left an emerald-growing experiment running in his father’s garage. When his father realized it, he turned off the power. Consequently, the emerald crystals grew inside the crucible.”

Carroll Chatham was perplexed and spent three years trying to understand why this had happened. After graduating from Caltech in 1935, he founded his own eponymous company and began commercializing man-made emeralds using the flux technique, which is still in use today. In 1965, Tom Chatham joined his father at the company’s lab in San Francisco, California, and became CEO of Chatham in 1976.

Over the years, other scientists have researched ways to grow emeralds, refining their techniques and creating equipment. “In the mid-1960s, Pierre Gilson in France perfected his synthetic emeralds using the flux method,” while Japanese manufacturer Kyocera did the same in the late 1970s, says Kane.

Each company operating today has its proprietary methods. At Chatham, “the process takes 12 months, and the growth rate is about 2 to 3 millimeters per month,” says Tom Chatham, adding that “none of the crystals are perfect or even near it; [that’s] a common misconception.” To get flawless gems, one has to remove as much as 80% of the rough. “Our average yield is 22%, compared to natural stones, where the yield is about 50%.”

The hydrothermal method of growing emeralds uses water instead of a chemical solution, explains Chatham. “It is super-heated to 500 degrees Celsius under great pressure.”

Decades ago, an Australian company used this method “to create unusually large clean crystals, sold under the Biron name starting in 1985,” comments Kane.

Today, Chatham is one of two major emerald producers using the hydrothermal method, according to the company CEO; the other is Bangkok, Thailand-based Tiarus, which manufactures in Siberia.

As for color, the Chatham-grown emeralds lean toward the bluish-green of Colombian specimens from the Chivor mine, though the company also produces the vivid-green hues of Muzo emeralds. Stones from Tiarus tend to be darker.

The main market for Chatham’s wares is the US. “Our advantage is simple. We can cut any size or shape,” explains Chatham. “We supply thousands of emeralds in specific calibrated sizes — e.g., a 7- by 5-millimeter octagon. You cannot do that with natural stones.”

Still, he stresses, “we have no fight with natural emeralds. Both natural and lab-grown have their own market, with little overlap.”

Article from the Rapaport Magazine - August 2021. To subscribe click here.