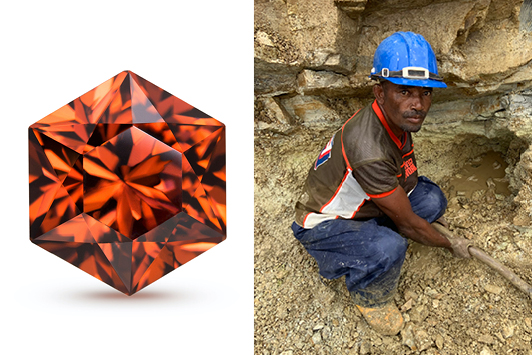

Images: Anza Gems; Prosperity Earth

Images: Anza Gems; Prosperity Earth

Ethics and transparency are a key part of membership in the

American Gem Trade Association (AGTA), so it’s little surprise that those who exhibit at the group’s GemFair Tucson event increasingly have clients ask about their chain of accountability; consumers want to know the backstories of their bling.

Returning to Tucson for live sales was a boon for both exhibitors and attendees of the February 1 to 6 show, as the pandemic had prevented the 2021 edition from taking place. There’s nothing like seeing and handling stones in person, or hearing a firsthand report on origin stories and how gems directly benefit source countries.

These accounts were readily available from people like the Shahs of

Prima Gems USA, who exhibited at the show and who take great pride in scrutinizing every aspect of their international, family-run business. With someone on the ground buying directly from mines in Africa and another overseeing a cutting factory in India, Jaimeen Shah knows his team is diligently working to improve the lives of its staff and everyone in the company’s supply chain. The family also only works with miners or brokers who have government clearance and verification that they are legally permitted to deal in gems.

“This is the direction the business is going in, and we are on our way to being above and beyond standard practices,” he says.

Attendance and transactions

Buyer attendance at the 2022 show was down 25% compared to 2020, according to former AGTA CEO Doug Hucker. However, this year’s exhibitors are quick to confirm that those who did make the trip were shopping hard.

“For us, traffic was even better this year than in 2020,” relates Jonathan Farnsworth, president of

Parlé Jewelry Designs. “And they weren’t just tire kickers. People were buying more and saying, ‘I need this or that.’ There was little price resistance.”

Sapphires — particularly Montana specimens — remained top sellers at the event, as they were in previous years. Indeed, loose Montana sapphires and finished jewelry account for about 10% of annual sales for Parlé, though they accounted for up to 50% of its sales at the Tucson show.

Montana material is the entire business model of fellow GemFair exhibitor

Potentate Mining, which owns more than 3,000 acres of land in the US state that gave the stones their name. Potentate has been mining sapphires at Rock Creek in Granite County, Montana, since 2014 — including sizable stones such as the 64.14-carat Ponderosa sapphire it unearthed in the summer of 2018. It is also one of the largest producers of teal sapphires, according to Potentate consultant Warren Boyd.

Sri Lankan sapphires, however, were trickier to come by at this year’s show. Sheahan Stephens, owner and CEO of the eponymous firm, says Covid-19 shut down most mining operations within the country, as well as sparking financial chaos — complete with inflation and price inconsistencies.

He has been unable to resume his philanthropic initiatives in Sri Lanka, which include training miners and cutters. However, he did still sell whatever stones he could access to a hungry American audience at GemFair Tucson. “Retailers [were] asking for teal green, bi-color and purple sapphires, and [for] padparadschas,” he says.

For Evan Caplan, who also has an eponymous firm, no-heat sapphires were equally hard to obtain; prices were “through the roof,” he reports. Other gems that were in demand included alexandrite, emeralds (including trapiches), rubellite, aquamarines, and Paraiba tourmalines from Brazil and Mozambique.

The challenge in sourcing that Windex-blue Paraiba material, says Caplan, is that “nothing is coming out of the ground.” Meanwhile, the biggest sourcing challenge overall is finding quality specimens and being able to afford them. “Prices are going up by the minute,” says Caplan, whose 2021 sales were double those of the previous year.

Eric Braunwart, founder of

Columbia Gem House, agrees. With color sales up and less rough on the market, the industry has a big problem that “it hasn’t entirely realized yet,” he maintains.

The path to traceability

Given the strict code of ethics to which AGTA members adhere, they are primed to be clear in both their approach to sourcing and the way they care for people in producer countries. And with each passing year, more Tucson show dealers unveil efforts to improve traceability.

Braunwart is a pioneer in this space. For 25 years, he has been buying stones directly from traceable sources and ensuring that producers are treated well and paid fairly. It hasn’t been an easy path, but it is one where he now sees momentum building.

“This year was like a whole new world,” he says. “From small companies to some of the largest in the industry, people came…to tell us that while what we are doing is somewhat more expensive, they can’t afford not to work this way anymore.”

His mine-to-market projects include sunstone from Oregon, black pearls from Mexico, and sapphires from Montana, Nigeria, and Australia — with more offerings from other international locations available soon.

Other dealer exhibitors have opened mines of their own to ensure both access to material and fair treatment of staff on site. For example, Caplan and his partner, Miriam Mimo Kamau of Mimo Gems, are just starting to produce tsavorite from a site in Kenya that they have owned for two years.

“We had 10 months of torrential rain, and then we had to drill through hard rock to make a tunnel,” Caplan says of the endeavor.

John Ferry, founder of

Prosperity Earth, has a demantoid mine in Madagascar with 50 full-time Madagascan employees, including security, chefs, miners and cutters. He is as committed to local environmental protection and community development as he is to his gems, which aren’t treated. Sometimes, doing business in the country means he has to withstand months-long government export bans for seemingly no good reason, but he sticks it out for the love of the gem. “It’s a product that is sustainably and ethically mined, and 95% of it is cut in Madagascar,” he says.

And while John Ford — creator of the John Ford Lightning Ridge collection — doesn’t own any Australian black opal mines, he can track the origin of just about every stone in stock back to a specific site, especially for larger gems. He’s confident about the practices of the miners who supply his goods; he makes them sign contracts declaring that they will adhere to ethical business practices and environmental laws. Plus, after a mine is exhausted and the grounds restored, “you’d never know mining happened there,” he asserts.

It’s a similar scenario for Renata Abrahami, partner at

ABC Gems, who has been an AGTA member for 35 years. She has been sourcing emeralds from Africa, Brazil and Colombia — hence the name ABC — for just as long. Abrahami, who also sells sapphires and alexandrites, buys directly from miners with whom she has long-standing relationships.

“You build trust with people; it’s such a small business that word gets around if you’re not ethical,” she explains. “You have customers because you are transparent, and in turn, you are selling the integrity of your suppliers.”

Article from the Rapaport Magazine - April 2022. To subscribe click here.