Image: Paul Sedawie.

Image: Paul Sedawie.

For millennia, opal’s dramatic plays of color have inspired writers and poets, with some cultures ascribing supernatural origins and powers to the gem. Its name comes from the Sanskrit úpala, or perhaps from the Latin opalus, meaning precious stone.

Opal’s popularity has waxed and waned over the centuries. It went from being a symbol of good luck in the Middle Ages to having a less auspicious reputation in the 19th century. In the early 20th century, it even became associated with bad luck. Today, however, opal has never been more positive or widespread.

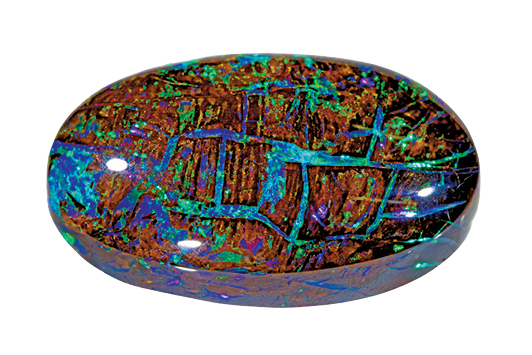

Opal is a hydrated, amorphous form of silica with a variable water content. In precious opal, the internal structure consists of tiny transparent or translucent silica spheres arranged in an orderly structure. When light passes through them, it is diffracted into separate colors, giving the appearance of surface scintillation. In common opal, the silica spheres are either too disordered or too compact to allow the light to refract a variety of colors. The gem may be opaque, transparent or translucent, depending on the conditions of its formation. The background may be almost any color, white or black, with black the rarest.

From Eastern Europe to Africa

Opal’s history dates to 400 BCE, when it was mined in Slovakia, according to Anthony Smallwood, opal appraiser and publisher of the Opal Academy website. The Aztecs used the stone in 850 CE in Mexico, and in 1893, it was mined at Opal Butte in Oregon. Occurrences in other states followed, most notably in Nevada, where the 23,587-carat Bonanza opal was found in 1976. Today, Mexico is still a source of opals, as are Brazil, Honduras and Indonesia, but Australia and Ethiopia are the predominant sources.

Opal was discovered in Ethiopia in 1993, near the headwaters of the Blue Nile. The 2008 discovery of deposits in the Wollo (Welo) province of northern Ethiopia was a game changer, and these Welo opals now occupy a major position in the global opal market. Today, opal accounts for 95% of the country’s precious-stone exports.

Of volcanic origin, Ethiopian opals come in both precious and common types, along with intermixing of both. Many are white to light yellow or translucent with a rainbow of body colors, but they also come in black with a kaleidoscope of hues. Ethiopian opals are hydrophane, which means they are porous and absorb water (unlike Australian opal). Because of this, sellers must focus on disclosure and education with consumers. While many are sold in their natural state, these opals may be dyed, smoked, or subjected to sugar/acid treatment. In smoke treatment, fine particles of black soot enter the gem’s pores, darkening its body, which contrasts more with the opal’s play of color. The sugar/acid treatment also produces dark stains in the body color. These techniques are detectable by testing.

“The stunning variety of body colors and vivid flash patterns in Ethiopian opals greatly exceeds that of Australian opals,” says Jeffery Bergman, CEO of Bangkok-based Primagem. “Of particular interest are the interlocking patterns referred to as honeycomb, lizard skin, or snakeskin.”

In terms of price, he reports, “Ethiopian opals are wholesaling in Bangkok for approximately 10% of the price of Australian opals, given equal size

and quality.”

In a survey of 20 dealers selling opals in Bangkok’s Jewelry Trade Center, “only one stocked Australian opals, and only a few hundred carats,” continues Bergman. “The dealers selling Ethiopian opals stocked from 1,000 carats to over 10,000 carats. Prices for non-smoked or non-dyed goods ranged from about $3 per carat for sub-carat sizes up to $100 per carat for top qualities in sizes of 50 to 100 carats. The majority of the 2-carat and larger sizes ranged from about $20 per carat to $40 per carat. There were lots of calibrated cabochons, calibrated faceted and beads.”

Mike Romanella of Arizona-based Commercial Mineral bought a lot of Ethiopian opal in 2009 as it was coming onto the market. “It is a beautiful and popular mass-market gem,” he says. “It started at $35 to $75 per carat wholesale, to $125 for high quality. Today, it is still inexpensive, around $300 per carat for very high grade and $60 to $150 per carat for medium quality, which makes up about 98% of goods.”

As for production, “about 200 small local co-ops in five districts in the Amhara region are engaged in opal mining,” says Biniyam Bekele from Ethiopia’s Ministry of Mines and Petroleum. The output was 2,000 kilograms in 2018, 1,764 kilograms in 2019, 1,487 kilograms in 2020, and 760 kilograms for the first two quarters of 2021. “Given a rough-to-cut average yield of 30%, every 1,000 kilograms yields about 1.5 million carats of cut gems. Thus, 2020 production would result in over 2 million cut carats of Ethiopian opals entering the world gem market,” he states. Of this, about 95% goes to India, and 5% to the US and Europe for trade shows.

Treasures down under

Before the arrival of Ethiopian opals, Australia accounted for more than 90% of the world’s supply. The main types from the continent are black opal from Lightning Ridge; boulder opal mainly from Quilpie, Yowah and Winton in Queensland; and crystal and white opal mostly from Coober Pedy, Andamooka and Mintabie in South Australia.

“When Ethiopian opal first came on the scene, it was a double-edged sword for Australian opal,” relates California-based wholesaler Joel Price, whose family has been in mining and cutting Australian opals since the 1970s. “Because it boosted eyes on all opals, it was good for Australian black and boulder opal sales, but not so good for dealers of white opal.”

Still, each Australian variety has its own characteristics and its own admirers, with prices that vary considerably. Black is often considered the most precious.

“The Australian opal industry is fairly small and is conducted by individual miners,” says Smallwood.

“We all know each other,” affirms second-generation dealer Matt Hopkins of Rhode Island-based Hopkins Opal, which sells primarily Lightning Ridge black opal. “This industry has always been about ethical sourcing, making the gem even more appealing.”

Covid-19 reactions

In Ethiopia, says Bekele, the pandemic had very little effect on opal mining.

In Australia, however, the impact has been “enormous,” according to Opal Association president Paul Sedawie. “Close to 70% of the opal industry closed, as there were no foreign tourists and trade shows were canceled around the world. The retail opal shops in Australia are finding it tough, and some have closed.”

Price, too, has observed difficulties. “People are still finding it hard to move stones around because of lockdowns and restrictions. Business stopped for six to seven months,” he says. And while “this year, we are seeing prices move up on limited supply, as demand is there,” the market “is still volatile.”

That said, Sedawie characterizes the mood as positive. “Rough prices have moved up since it started,” he says, and because of the restrictions, online sales have seen dramatic growth. “The large online platform Opalauctions.com offers opals and opal jewelry from around the world and has reported a huge increase in sales, with more than 560,000 stones and parcels sold since it started.”

Hopkins agrees that “the internet has brought opal to the attention of many more people. It is a personal and dynamic type of stone. In the US, demand has gone up as people realize its uniqueness and rarity, especially black opal. While prices have gone up at the source, we have been able to keep reasonable margins to keep the gems flowing.” There have been no major issues in his bread-and-butter supply, even with limited travel from Australia, he adds. “But the very high end is becoming more difficult to find.”

Of fame and fossils

Set in jewelry, opals are exquisite, regardless of provenance. They also lend themselves well to carving, with some artists gaining international fame. The designs may be freeform or depict a particular subject. Terry Coldham, CEO of Australia-based Intogems, specializes in Australian opal carvings and believes they add a layer of artistry.

One big boon to the Australian industry is the Discovery Channel series Outback Opal Hunters, which started in 2018 and is currently in its sixth season. Broadcast in over 100 countries, it follows miners across the various opal fields in Australia, bringing not only increased awareness to the nation’s gem, but also new miners who come to try their luck.

Among the rarest opals are opalized fossils from Australia’s most famous opal sources — namely Lightning Ridge, White Cliffs, Andamooka, Coober Pedy, and the Queensland boulder opal fields, according to Jenni Brammall, special projects officer at the Australian Opal Centre (AOC). “They include teeth, bones, shells, pine cones and other remains of animals and plants that lived in Australia 96 million to 110 million years ago, during the age of the dinosaurs. Scarce, spectacular and often of great scientific value, they’re packed with clues to enduring mysteries about the history of life on Earth,” she says.

There is a growing market for these fossils, continues Brammall, who sees prices rising as supplies decrease. Because of their rarity and scientific significance, however, the Australian government prohibits exporting them without a permit, which can be obtained for some opalized fossils that are well represented in public collections in Australia. One of the most important such collections is at the AOC in Lightning Ridge, a national monument that intends to become a world hub for opal-related activities.

“The future is very upbeat for our industry,” declares Sedawie.

Article from the Rapaport Magazine - December 2021. To subscribe click here.