Sitting in his office in the headquarters of Shree Ramkrishna Export in Surat, company founder Govind Dholakia takes a philosophical view when explaining the Indian diamond industry’s exceptional growth through the past year. “Problem is progress,” Dholakia quipped. “If there is a problem, we see it as an opportunity to progress.”

As a former Diamond Trading Company (DTC) sightholder, Dholakia brings his own De Beers experience to illustrate the point. “We couldn’t understand why we lost our sight in 2008, as we’re a Top 10 manufacturer in India, but we took it positively because we believe that whatever happens in life, is for the good,” he explained. “And, although we were not a DTC sightholder, 2009 was a good year for us and we weren’t too affected by the recession.”

With DTC boxes selling at extremely low premiums, Shree Ramkrishna was able to buy large volumes of rough from sightholders and other sources in the market at cheap prices in the first quarter of 2009. The company took the opportunity to buy rough at 42 percent below prices seen in 2008, and the subsequent polished was sold at around 75 percent of 2008 prices. “In my 46 years in the industry, I’ve never seen anything quite like it. It was a gift from God.”

The company was not alone in this experience, and others, with the liquidity to do so, took advantage of the opportunity to buy high volumes of rough while the getting was good. Akshay Mehta, a director at Blue Star, explained that while the overall market focused on destocking in 2009, those who kept manufacturing were able to profit in the long run.

The result has left many of the larger, local manufacturers in a strong, liquid position in the current market — able to ramp up production and expand their operations while their counterparts in Antwerp, Ramat Gan and elsewhere take a far more cautious approach.

Coping With Crisis

However, the rapid recovery in Surat, India’s diamond manufacturing center, and in Mumbai, its trading hub, reflects factors far beyond the opportunism of its mainstay companies. Most attribute the minimal effect the recession had there on two factors that were lacking in other markets: the organized response of the Indian industry and the strength of the domestic market for jewelry.

Vasant Mehta, chairman of the Gem & Jewellery Export Promotion Council (GJEPC), noted that in the days before the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy filing in September 2008, the industry was growing at a healthy rate. GJEPC data indicate that polished exports rose 18 percent in the nine months that ended on September 30, 2008, from the same period a year earlier, while rough imports increased 14 percent.

Riding the 2008 bull market, manufacturers had built up inventories in anticipation of the U.S. Christmas season, Vasant Mehta explained. Therefore, after the initial shock of the downturn settled in, the industry realized that it had to act collectively to rethink the future, he recalled.

The Indian diamond sector put a moratorium on all rough imports for one month — through December 2008 — “in order to ease pressure on the pipeline,” Vasant Mehta explained. “We weighed that against the effect of jamming the pipeline.” The freeze on rough imports gave the trade time to digest the recession, and, as a result, by December, most understood what they were dealing with, he added.

Still Benefiting Today

While Vasant Mehta insists the Indian diamond industry is still benefiting from that decision today, it would have been difficult to foresee that outcome in the early, dark days of the downturn. Rohit Mehta, president of the Surat Diamond Association (SDA), reported that approximately 250,000 diamond workers — more than half the manufacturing sector — lost their jobs. Factories mothballed their operations or closed completely. While there was a mass exodus to the textile and agriculture sectors in Surat, many remained unemployed, and a string of recession-related suicides by diamond industry workers ensued.

Vasant Mehta said that after the moratorium was lifted in January and February, the industry was operating at 20 percent of its regular manufacturing capacity, and a slow and steady increase began in March. “Today, we are at about 80 percent of prerecession levels and we will reach 100 percent soon,” he said.

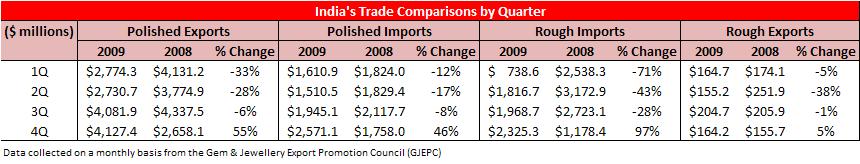

The steady improvement was evident in GJEPC data, which showed a steady rise in the country’s diamond trade (see table below). Polished exports by value fell just 8 percent to $13.71 billion for the full year, while by volume, they rose 3 percent to 44.086 million carats. In contrast, Belgium’s polished exports by value dropped 30 percent to $8.63 billion in 2009, and Israel’s decreased 37 percent to $3.92 billion.

Banking Support

As the year progressed and the global economy slowly improved, Indian manufacturers expanded their appetite to buy rough, leaving other centers behind. While the larger companies had the existing liquidity to do so, many attributed the industry’s capacity to buy to support from the local banking sector. “The Indian banks have been very cooperative,” said Anil Shah, chairman of Venus Jewels. “But it’s a two-way relationship and the diamond industry showed minimal loss for the banks through the downturn, compared to other industries.” Shah noted that the availability of dollar financing helped hedge the volatility in the rupee exchange rate.

The GJEPC’s Vasant Mehta agreed that the banks displayed confidence in the local diamond sector. “They realized that we have a healthier sector, and that proportionally, India has an effect on the diamond market,” he said, reporting that industry bank debt fell from about $5.5 billion before the recession, to a sanctioned limit of $5 billion today, of which approximately $4.34 billion is being used.

One financier, who requested anonymity, noted that none of the larger companies have needed to extend their borrowing lines with the banks and that they are now in a position to increase sales and decrease their debt. He doesn’t believe the Indian banks are more liberal in their lending than those in other countries, but that their support rather stems from the importance the country as a whole places on India’s export industry in general, which extends to banking policy.

The Domestic HedgeAfter years of growth, India’s exports fell approximately 18 percent to an estimated $165 billion in 2009, according to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) World Factbook, as the downturn brought about a slump in international demand for the country’s products. At the same time, the CIA estimates that the local economy grew by about 6.5 percent in 2009. Consistent growth over the past decade has resulted in a new domestic affluence, which has filtered to the diamond industry.

Vasant Mehta explained that when the recession hit, the industry soon realized that it could use the growing local market to buffer the drop in international demand. This realization was brought home after the 2008 Diwali season, the festival during which it is traditional to buy jewelry, which occurred just over a month after the Lehman Brothers collapse. “Diwali saved us that year,” Vasant Mehta said. “We were lucky to have the domestic market during the recession. It propped us up during a difficult year internationally.”

The domestic Indian jewelry market has an estimated value of about $30 billion in fiscal 2010, of which diamond jewelry accounts for about 20 percent, according to Ashok Mehta, chairman of the All India Gems & Jewellery Trade Federation, an umbrella body for the local jewelry industry. He estimated that the domestic market grew 15 percent through the recession, adding that “we expect 2010/2011 to be phenomenal for the industry and the biggest growth will come from diamonds.”

A New Syndicate

Signs are that he may be right, and that his prediction extends across the diamond manufacturing sector. According to SDA’s Rohit Mehta, manufacturing has already returned to full employment, with a shortage of workers developing in Surat.

More telling, Indian traders have continued to move the market, largely dominating activity at the March Hong Kong International Jewellery Fair. Polished exports grew 77 percent through January and February 2010, compared to 2009, and surpassed January/February 2008 levels by 17 percent.

These trends have diamantaires in other centers concerned. “The Indians are leading the market and have a monopoly of sorts,” said one Israeli polished dealer. “They pay top prices for rough, and when we sell polished to them, they pay top prices, which others cannot match.”

Similarly, manufacturers in Israel and Belgium cannot understand how their Indian competitors are able to profit on the rough prices they pay, and blame them for the speculative bubble that may be developing. “There even seems to be some kind of new Indian syndicate at work because the market there almost unanimously accepts new prices,” said another manufacturer.

Vasant Mehta acknowledged that the Indian market has played its role in driving rough prices higher but cautioned that the Indian sector is guilty due to its sheer size. “Our market share is 55 percent by the value of global polished production, and 90 percent by volume, so it’s not that we’re guiltier than anyone else. It’s all in proportion.”

And is there an Indian syndicate of sorts that has pulled the industry out of recession? “There’s a form of syndicate but it’s not coordinated,” said Shah. “It’s a natural economic development,” a development, clearly, that has left other centers, and the recession, behind.

Editor's note: Corrections have been made to the quotes by Govind Dholakia, of Shree Ramkrishna Export. Please note that the present version is correct and previous misquotes should not be viewed as a miscommunication by the company.

Article from the Rapaport Magazine - April 2010. To subscribe click here.