RAPAPORT...

RAPAPORT... When it comes to synthetics, the diamond industry has — to borrow a term from management consultant Geoffrey Moore — crossed the chasm.

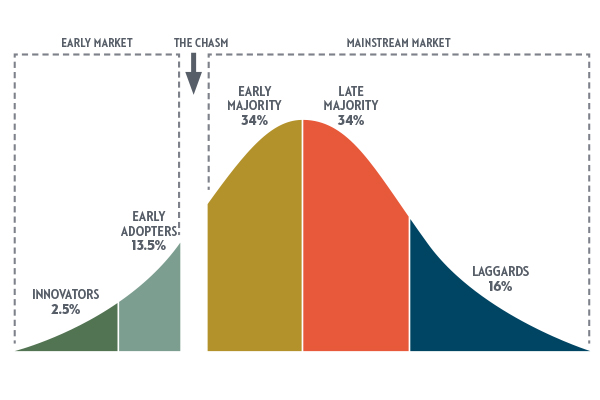

Crossing the Chasm is the 1991 book in which Moore discusses how to sell innovative high-tech products to mainstream customers. The titular chasm refers to the enormous gap between the “early adopters” and “early majority” stages of a new product’s acceptance in the market (see graph). It is the phase when a product is highly disruptive and requires behavioral changes, and it’s a point that most hyped-up technologies struggle to pass.

Everett Rogers's innovation adoption life-cycle bell curve, as cited in Geoffrey Moore's book Crossing the Chasm.

Everett Rogers's innovation adoption life-cycle bell curve, as cited in Geoffrey Moore's book Crossing the Chasm.

While the lab-grown market underwent a drawn-out phase of innovation — starting when General Electric announced the first proven synthetic diamond in the early 1950s, and then its first gem-quality stone nearly 20 years later — the sector only started to make inroads in the mainstream market during the past decade. It is now arguably in the early-majority phase as more jewelry retailers, wholesalers, and diamond manufacturers enter the space.

But it hasn’t been a smooth ride toward acceptance. Many in the wider jewelry industry — the “laggards,” as the graph would call them — continue to view lab-grown as a pariah. Still, attitudes have changed toward the product, which the trade considered its biggest threat not so long ago.

Preparing for battle

In May 2012, the diamond industry got its first real lab-grown scare: The International Gemological Institute (IGI) found hundreds of undisclosed synthetic diamonds that had been submitted to its Antwerp and Mumbai grading labs as natural specimens.

The shock stemmed not only from the revelation of the biggest fraud to date relating to undisclosed lab-grown, nor just from the IGI’s warning that a large volume of these stones might already have entered the market. The discovery also signaled that the synthetics sector was starting to make waves, that production was rising, and that the natural market might not be prepared for the fight.

Indeed, a battle ensued in those early days. There was a clear division within the market between lab-grown companies and natural-diamond ones, with very little overlap.

The major diamond centers, including India, Israel and Belgium, banned synthetics from their trading floors — and in some cases, their bourses’ entire premises. The wider trade focused on detection, with De Beers and the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) leading the race to stay ahead of the fraudsters and take a share of the budding detection-equipment market.

Natural predator?

Meanwhile, the lab-grown companies went on the offensive in their marketing, adopting the message that their product was a greener, more environmentally friendly alternative to mined diamonds.

And the natural industry took the bait. Synthetics were the implied target when the Diamond Producers Association (DPA) launched in 2015 with its “Real Is Rare. Real Is a Diamond” campaign slogan.

However, the barriers gradually started to crumble as jewelers came to view synthetics as simply another jewelry category, even if it was positioned as an alternative to natural diamonds. Louisiana-based Stuller Inc., one of the largest jewelry wholesalers in the US, was the first major company to make the move toward synthetics, adding them to its product list in early 2016.

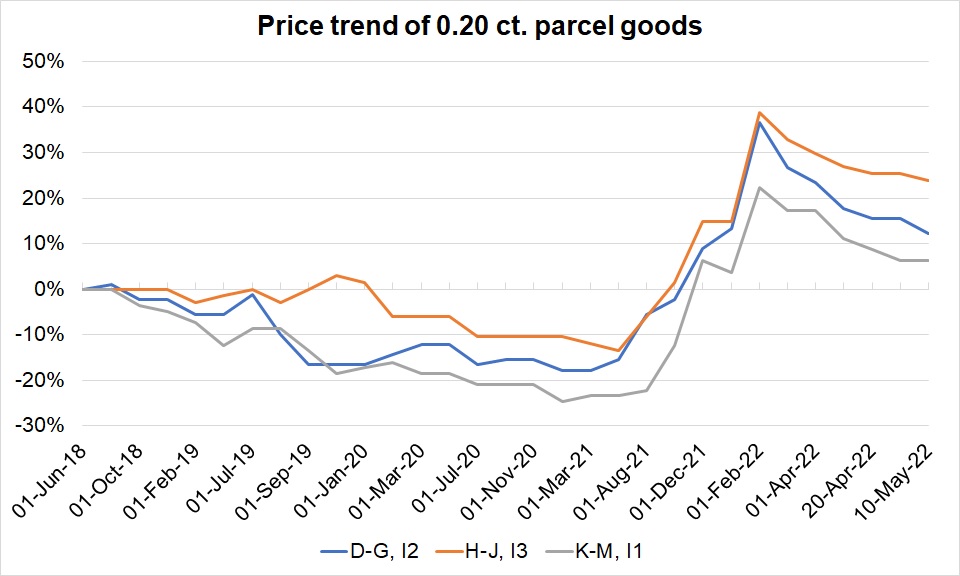

At the time, analysts at Morgan Stanley suggested that the biggest threat from lab-grown lay in the melee market. The firm predicted that synthetics would take 15% of the small-stone segment, which would have a negative impact on prices. So far, the melee sector has stood up to the perceived threat, with prices jumping 50% in some categories last year (see graph).

Based on Rapaport Research

Based on Rapaport Research

But that trend may not continue in today’s reality. With Russian diamonds off the market due to sanctions over the war in Ukraine, jewelers may yet turn to lab-grown to fill the expected supply gaps. Notably, Morgan Stanley observed even back then that the growth of synthetics was a greater threat to Alrosa than to De Beers, since the former had a higher proportion of melee in its total production.

Turning point

The industry’s watershed moment came in mid-2018, when De Beers unveiled its Lightbox brand, marking the company’s entry into the lab-grown market, and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) expanded its definition of “diamond” to include those created in a laboratory. Lab-grown required a descriptor for marketing purposes — though that term should not be “synthetics,” the FTC specified.

These developments gave the sector two stamps of approval: one from a regulatory body, and one from the world’s biggest diamond brand — even if De Beers’ purported goal was to keep lab-grown contained. By setting its price at a standard $800 per carat, De Beers positioned the product as a fun, low-cost fashion-jewelry item — i.e., not suitable for bridal.

For the rest of the industry, those two events changed the debate surrounding synthetics. More companies began including them in their inventory. The conversation shifted from the macro question of lab-grown’s legitimacy to micro issues surrounding its appearance on the market. Five main themes shaped the discussion: nomenclature; disclosure of post-growth treatments; grading and quality control; pricing; and marketing.

1. Nomenclature

The World Jewellery Confederation (CIBJO) took issue with the FTC’s ruling on lab-grown terminology. The trade group — which sets policy for the jewelry industry with the aim of protecting consumer confidence — classified a diamond as a material formed by natural means, without human intervention. CIBJO argued that lab-grown was an artificial product — even if it had essentially the same chemical composition as a diamond — and therefore should not be included in the definition of the term “diamond.” Furthermore, CIBJO permitted the use of “synthetics” as a descriptor for the product.

2. Disclosure of post-growth treatments

CIBJO also recommended full disclosure of any treatments the stone underwent in the growth process. While the GIA includes treatments in its lab-grown reports, De Beers initially argued that post-growth treatments were part of the process and were therefore unnecessary to disclose. When growers used the chemical vapor deposition (CVD) method to produce the stone and subsequently enhanced it with High Pressure-High Temperature (HPHT) treatment, both of these were steps in the stone’s creation, De Beers reasoned.

While the company has since started to disclose post-growth treatments, the message behind its initial stance signaled an important difference within the market — one that still exists today. For De Beers, man-made diamonds are not a precious luxury item like natural ones; they are simply another jewelry product.

3. Grading and quality control

In keeping with that view, De Beers believes lab-grown requires quality control, not a grading report. After all, a grading report implies that the product has a degree of rarity, which lab-grown doesn’t, according to CIBJO. As such, CIBJO proposed the name “Laboratory-Grown Diamond Product Specification” for the document detailing synthetics’ qualities. It also suggested placing a notification of “LG” next to the color and clarity descriptions.

The GIA dismissed the CIBJO directive, going all in with its renamed Lab-Grown Diamond Report. Most significantly, the GIA started giving specific color and clarity grades for man-made diamonds, rather than a range as it had previously done. This move aligned its lab-grown reports with its natural ones and with the FTC’s concept of a diamond, de facto distancing itself from CIBJO’s idea that a grading report implies rarity.

4. Pricing

The widespread grading of lab-grown diamonds encouraged companies to continue selling them based on natural prices — that is, at a discount to the Rapaport Price List. However, De Beers took a different approach. Since the product didn’t have the same rarity as natural, the company maintained, it required a more standardized pricing mechanism. It costs the same to produce a D-color, VVS1-clarity stone as it does a G, SI2 stone; therefore, their pricing should be consistent. This was De Beers’ rationale for its $800-per-carat price tag.

Besides, pegging lab-grown prices to natural-diamond ones will inevitably lead to a decline in the former as supply increases. India’s manufacturing sector — which accounts for about 15% of global polished lab-grown output, according to the Gem & Jewellery Export Promotion Council (GJEPC) — is seeing massive gains in the synthetics segment.

The country’s net exports of lab-created polished more than doubled in 2021 to $1.11 billion, continuing the momentum in 2022’s first quarter with a 77% year-on-year jump to $362.7 million. The council has appealed to the government to invest in the sector — both to capitalize on its growth potential and to make up for the dwindling availability of natural stones.

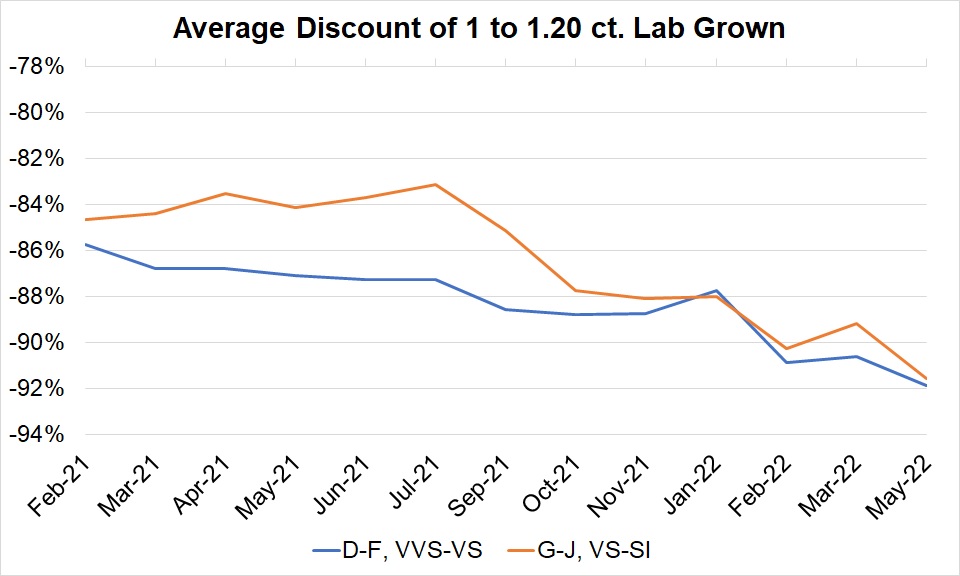

As the supply of synthetics increased during the last year, wholesale prices declined. In May, 1- to 1.20-carat, D to H, VVS to VS lab-grown goods were trading at average discounts of about 92% to the Rapaport Price List, compared to around 86% at the beginning of 2021 (see graph). Retailers continue to see strong profit margins of about 47% for the same size and quality categories, based on prices at jeweler Brilliant Earth. The same has been true for other sizes.

Based on wholesale lab-grown prices obtained by Rapaport. Average discount refers to the average percentage below the Rapaport Price List for the equivalent natural diamonds.

5. Marketing

Based on wholesale lab-grown prices obtained by Rapaport. Average discount refers to the average percentage below the Rapaport Price List for the equivalent natural diamonds.

5. Marketing

The solid margins suggest that jewelers are selling lab-grown as an alternative to natural diamonds. Anecdotal reports corroborate this theory, be it in fashion jewelry or higher-priced bridal. Yet both products have become less combative in their marketing in recent years.

Lab-grown companies recognize that if they want to provide a responsibly sourced product, they need to meet the environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards expected of the natural-diamond industry. Perhaps their attitude changed when the FTC called out marketers of synthetics for making false claims about natural diamonds’ impact on the environment.

Meanwhile, the natural diamond industry has recognized that it has virtues of its own to champion and doesn’t need to be reactive to the synthetics market. This has been evident in the rebranding of the DPA to the Natural Diamond Council (NDC), and its subsequent campaigns.

The result is that both segments had a stellar year in 2021. Projections show the lab-grown market continuing to expand at an impressive pace, particularly considering that it’s still in the early stages of the innovation adoption cycle. Man-made diamond production reached 6 million to 7 million carats in 2020, according to Bain & Company’s Global Diamond Report for the period. By comparison, 2020’s natural rough output came to 107.8 million carats, per Kimberley Process data.

Competition or complement?

There are still more retailers waiting to jump in and offer synthetics to consumers who are unaware of the option or of what the difference is between the two products. That’s where the next challenge for the industry lies, and where the debate about lab-grown has arrived in 2022.

With lab-grown currently expanding through the majority phase of the adoption life cycle, will it compete with or complement the natural-diamond market? Much depends on supply and its relationship to price. As technology improves, synthetics production will rise. And as supply increases, prices will naturally come under pressure.

Definitions aside, the two products do have different value propositions. Lab-grown diamonds will not hold their value over time in the same way natural diamonds do; they will lose it, because they are producible in unlimited quantities. That is the final disclosure that retailers need to make to consumers.

Indeed, promoting the sale of synthetic diamonds without conveying their inability to store value is threatening the integrity of the natural diamond industry, Rapaport Group Chairman Martin Rapaport contended in his “Synthetic Ethics” article from the June 2019 edition of

Rapaport Magazine.

“Consumers are being misled about the medium- and long-term value of their synthetic diamonds,” he stated. “Absent full and fair disclosure, it is likely that once consumers find out about the value retention problem, they will no longer be interested in buying any diamonds, including natural diamonds.”

That’s an outcome neither segment wants. Amid the hype of rapid expansion, sellers of lab-grown have the power to shape the future of both markets. As such, being transparent about the qualities and value of lab-created goods is in everyone’s best interest.

Image: Set of round and fancy-shape, lab-grown diamonds. (Keystar)

Article from the Rapaport Magazine - June 2022. To subscribe click here.