|

In-Depth

The Diamond Promise

How Rio Tinto and De Beers are leading the drive toward social responsibility.

By Ricci Dipshan

|

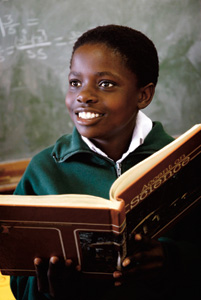

On some community outreach programs, Rio Tinto works in cooperation with such organizations as United Nations International Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

Photo courtesy Rio Tinto Diamonds. |

In the push for sustainable and ethical development in the diamond and jewelry industry, an old adage is ringing true — “If you want something done right, do it yourself.”

While there are umbrella organizations with broad scope and reach that deal with sustainability and ethical issues, many companies are taking it upon themselves to implement and promote socially responsible practices within the industry. Such efforts are particularly significant when undertaken by some of the largest and most influential companies. A case in point is Rio Tinto and De Beers leadership in the area of social advancement. The two companies’ initiatives have not only had an unprecedented impact on the diamond and jewelry market but their actions are arguably one of the strongest factors compelling the rest of the industry to adopt sustainable and ethical practices.

|

| Rio Tinto’s Bunder Project initiatives reflect the wide range of needs in the area, including help with agricultural practices. Photo courtesy Rio Tinto Diamonds. |

The most well-known and advanced social responsibility campaigns from these companies — Rio Tinto’s Bunder Project and De Beers Forevermark brand — stand as encouraging and imitable success stories for future social advancement efforts.

Tarun Malkani, chief operating officer (COO) of Rio Tinto Diamonds India, knows exactly where his company stands in the movement toward socially responsible practices. “Rio Tinto,” he declares, “has been a prime mover in marshaling the global minerals industry to support sustainable mining. We are in the business of creating value by finding and developing new, world-class deposits and operating and eventually closing them safely, responsibly and efficiently. To do this, we must take a disciplined approach to the economic, social and environmental aspects of all our activities. Our business success and reputation depend upon it.”

Rio Tinto’s social responsibility agenda, says Malkani, “comes from the top. Our board and senior management firmly believe that a sustainable approach adds shareholder value.”

Nowhere is Rio Tinto’s social responsibility effort more visible than in its first and most advanced mining venture in India, the Bunder Project. The area around the mine in central India is home to some of the country’s most impoverished communities. “The Bundelkhand region in Madhya Pradesh where the mine is located is disadvantaged,” says Malkani. “The population has very limited access to health, education and communication services, child malnutrition rates are high, illiteracy rates are high and the largely infertile land they rely on is often subject to drought.”

It is noteworthy that Rio Tinto’s social and community work in the area of the mine began far in advance of any mining operations. Mine construction at the Bunder Project site is slated to take place from 2014 to 2015, with the mine becoming operational in 2016. But the company has been actively engaged in outreach and development in the project area for almost a decade. Diamonds were discovered in the region in 2004 and a prospecting license executed in 2006.

“From the early days of the project, we’ve had community relations staff on the ground, collecting information about local needs and circumstances and building constructive relationships with local communities,” explains Malkani. “That’s a very important aspect of our work here and we will have been working with communities on the ground for 12 years before a single diamond is commercially produced.”

One of the most immediate benefits from the mine — and a core part of Rio Tinto’s social responsibility strategy — is local training and employment. “The Bunder Project currently employs approximately 420 people, including contractors, 85 percent of whom are from Madhya Pradesh. This figure will likely double during the construction phase,” says Malkani. “Over time, direct employment from a fully operational diamond mine is anticipated to be some 400 employees, with hundreds of other community jobs involved in providing the necessary goods and services that support a mine.”

Fostering employment also means keeping a workforce healthy and in shape. Toward that goal, Rio Tinto provides on-site health services for Bunder Project workers and their families, which includes access to a gym, recreational facilities for sports, yoga and meditation, access to healthy daily meals and a “be active” physical training program.

The company’s health efforts, however, do not end there. Rio Tinto also supports and reaches out to other health groups already established in the area to tackle some of the toughest challenges facing the communities. One example is the company’s work with HIV/AIDS initiatives in the region. “We have worked with a local group to help educate the communities about HIV/AIDS,” states Malkani, adding that the company also sponsors a traveling AIDS awareness show. “The show was developed in consultation with local and national AIDS organizations and is performed by locally trained theatre artists in public spaces.”

|

Rio Tinto’s social investment in India is unbiased and inclusive — it aims to help everyone in the community, regardless of caste, religion or gender. It is therefore no surprise that some of its efforts are progressive and trailblazing — especially with regard to its work with women. The company reached out to women through workshops that discussed “a range of topics associated with health, nutrition, childcare and employment, including how flexible employment arrangements with the mine can help to make Rio Tinto a key driver of women’s employment in the region,” says Malkani.

Acting on the feedback it received, Rio Tinto soon enrolled women in its driver-training program and subsequently employed them as drivers. “Given that female drivers are a rare phenomenon, even in metropolitan India, the program has been quite groundbreaking in terms of broadening attitudes toward women. Even if they don’t take a job as a driver at the mine, the women are learning useful life skills that they haven’t had access to before, and they feel empowered by that,” points out Malkani.

Tantamount to Rio Tinto’s health and employment efforts is promoting education among children and teenagers in the communities around Bunder. Chief among these efforts is tackling the region’s high rate of school dropouts, especially among children and young women. A part of the effort includes coaching centers, which have been started in five nearby villages, to counsel students at risk of dropping out. The program was so successful that Rio Tinto soon expanded these centers to other villages in the region.

The company also stepped in when a school in the remote village of Dardonia in the forests of Madhya Pradesh was set to close in 2008 due to low student enrollment. The company adopted the school and provided aid to keep classes running while it successfully negotiated with local and state education authorities for the school to be officially reinstated.

“Saving the school was a tough battle, but one worth fighting,” says Malkani. “Given that the only alternative for the school’s 30 or so students was to travel several hours by foot to the nearest primary school, this was an important thing for us to do.”

There are also efforts underway to educate the native populace on Bunder Project and provide them with the skills to work at the mine. For example, Rio Tinto runs a program where it links school graduates with government-run training institutions so they can develop the specialized technical skills needed to work at the mine site. The company also distributes activity books for children that explain the project itself, providing “a child-friendly account of what modern diamond mines do, what they look like and what jobs they involve.”

To further heighten its visibility, Rio Tinto supports street theater productions in the communities. “They can be a very powerful communication tool where literacy rates are low,” explains Malkani, adding that the productions have “reached an audience of approximately 12,000 people in 32 different locations.”

Rio Tinto’s social responsibility efforts are not limited to Bunder. In fact, the company’s efforts at Bunder are built upon its experience with similar efforts at other mine locations, like the Murowa mine in Zimbabwe. “In the relatively short time it has been operating at Murowa, Rio Tinto has done a lot to help improve local agriculture and livestock yields, to improve local schools, build health clinics and encourage AIDS awareness and testing,” says Malkani.

Similarly, Malkani says “At the Diavik mine in Northwestern Territories, Canada, and the Argyle mine in the Kimberley region of Western Australia, there has been enormous investment in training, employment and business development opportunities for indigenous people to help them improve their long-term prospects” for employment, self-sufficiency and a higher standard of living.

In many ways, De Beers social responsibility strategy is much like that of Rio Tinto — reaching out to communities with programs and support focused on health, education, employment and local development to create value for the areas in which its mines operate.

In 2011, around 87 percent of De Beers more than 12,000 global employees were Africans, and the company spent approximately $18.3 million that year on local job training. In many countries in which it operates, the De Beers workforce is predominantly historically disadvantaged employees — especially in South Africa, where the disadvantaged demographic makes up 87 percent of the company’s local workforce.

Like Rio Tinto, De Beers aims to employ more women in a traditionally male-orientated industry. Its efforts have yielded substantial results — from 1996 to 2006, the number of women in the workforce at its mines in Canada increased by 44 percent. In 2011, women made up 23 percent of its global workforce and held approximately 31 percent of its management positions.

In total, De Beers spent $34.7 million in 2011 on social investments, the majority of which went to communities in Botswana, Namibia and South Africa. The company’s biggest social investments were in such health incentives as HIV/AIDS education programs and services and on-site and local health services and infrastructure.

Because De Beers mining operations can sometimes disrupt villages, it also invests heavily in housing initiatives and develops relocation plans with surrounding authorities. Through a Resettlement Action Plan, for example, De Beers relocated 72 people from a small town in Angola to an area nearby, providing them with new eco-friendly homes, compensation for any loss of crop revenue, a “disruption allowance” and replacement farmland.

Pivotal to the company’s social investments is also its education outreach. Indeed, on-site schools and support for educational institutions and initiatives were the company’s third-largest investment in 2011, behind health and housing expenditures.

What differentiates De Beers social responsibility efforts from others, however, is the innovative strategy it has employed with its Forevermark brand diamonds, which are marketed with the promise that they are “beautiful, rare and ethically sourced.” Forevermark is able to keep this promise, explains Jamie Clark, De Beers business integrity manager, because “the majority of Forevermark diamonds originate from the De Beers Group.”

While the majority of Forevermark diamonds are mined by De Beers, the company also opens up the Forevermark brand to other mining companies, thereby forcing them to adopt similar socially responsible practices. “The De Beers Group leads the way in implementing responsible business practices in diamonds through its Best Practice Principles Assurance Programme, not just in its own operations, but as a condition of doing business with others,” says Clark. “In this way, we are encouraging and promoting sustainable ethical mining and social investment.”

Clark explains that Forevermark starts its search for mining partners by screening home countries on such variables as: “Kimberley Process (KP) membership, a positive and proven human rights record, a stable and acceptable political climate and likewise, a stable and acceptable socioeconomic situation.”

In countries that meet these basic criteria, Forevermark next investigates local mining companies, which “must meet a number of specific criteria, such as listing on a reputable stock exchange belonging to the World Council of Exchanges, and membership in the Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC),” says Clark. “The company must also publish an annual report and its ethical policies must be publicly available.”

After a company meets these prerequisites, Forevermark then examines key areas of company management and employee welfare in terms of safety and security, as well as benefits such as training and education. “We also analyze the positive cumulative effect the mining company has had on the local area, looking at local health provisions, such as health centers, as well as equipment, education and training funded by the company,” says Clark.

One company that met those Forevermark standards was Rockwell Diamonds Inc., located in Barkly West, in the Northern Cape Province of South Africa. Rockwell Diamonds especially stood out, explains Clark, for its funding of the Barkly West orphanage, its work with education officials to support a nearby high school and its boarding facilities, and its sponsorship of daily meals and computer centers at three other schools in the area.

With Forevermark, the mining is just one part of the brand’s promise. Cutting and polishing is the second. “Just as a Forevermark diamond can only come from an approved mine, it can only be cut and polished by an approved Forevermark Diamantaire,” declares Clark. “Of all the cutting and polishing companies in the world, only 31 are eligible to apply their master craftsmanship to unleash the beauty of a Forevermark diamond.”

These diamantaires, Clark explains, must abide by “Forevermark’s proprietary Pipeline Integrity Standard. This is a system that allows us to track and trace each Forevermark diamond continually throughout its journey from a mine to a store. The Pipeline Integrity Standard was developed in conjunction with the British Standards Institution, and every Forevermark Diamantaire is tested against this process by our third-party auditor Société Générale de Surveillance (SGS) on an annual basis without exception.”

|

De Beers diamond revenues help assure that every child up to the age

of 13 receives a free

education in Botswana. |

One of the core principles in De Beers and Rio Tinto’s social responsibility efforts is that to really make a difference and promote sustainable and ethical trade, companies must go above and beyond merely tracking their product’s origin.

“It is an important element of the Forevermark promise that our diamonds are not only sourced from producer companies that comply with our strict political, financial, social and environmental requirements, but that they go beyond this and actually benefit the communities in which they are operating,” says Clark.

While ongoing efforts by De Beers and Rio Tinto can serve as a template for other companies looking to expand their social responsibility activities, there is no doubt that such activities are arduous and have to be custom-tailored to specific locations. “Given the diversity of Rio Tinto’s operations and its geographical spread, this may seem a complex task. In fact, it is — but experience has taught us the importance of local solutions to local problems,” concludes Malkani.Article from the Rapaport Magazine - March 2013. To subscribe click here.

|

|