|

|

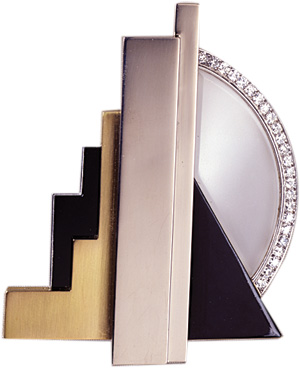

Gold, onyx, lacquer, rock

crystal and diamond brooch,

1925, French, by Jean Fouquet, Toledo Museum of

Art,

Mr. and Mrs. George M. Jones, Jr. Fund.

|

Before the worldwide web was even a blip on the horizon,

world’s fairs offered an international showcase for participating countries to

share with a global audience what was considered cutting edge at the time. They

celebrated ingenuity and creativity, as embodied in the thousands of objects

put on display.

A new exhibition, “Inventing the Modern World: Decorative

Arts at the World’s Fairs 1851–1939,” is co-organized by the Nelson-Atkins

Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri, and the Carnegie Museum of Art in

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It offers a rare look back at the wonders that were

offered at the world’s fairs and international expositions from the London

Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations of 1851 through the

New York World’s Fair of 1939.

JEWELRY A STAR ATTRACTION

“Jewelry was an essential component of the world’s fairs

from the very beginning,” says Catherine L. Futter, Ph.D., The Helen Jane and

R. Hugh “Pat” Uhlmann curator of decorative arts for the Nelson-Atkins Museum

of Art. The world came together in one place at these fairs and presented what

Futter describes as extraordinary “top-of-the-line” objects.

For jewelers, it was an opportunity to showcase not only

current design trends or new manufacturing techniques but also new materials.

Tiffany & Co. started showing at world’s fairs early on and had huge

displays, says Futter. “The 1939 New York fair had lots of jewelers. Tiffany

was promoting champagne diamonds and we have in the exhibition the floral

brooch with white and yellow diamonds that illustrates that.”

These world’s fairs were also about nationalism and

international competition — “our things are better than your things,” says

Futter, who co-curated the exhibit with Jason T. Busch, curatorial chair for

collections and The Alan G. and Jane A. Lehman curator of decorative arts and

design at the Carnegie Museum of Art.

For example, Futter says, “a beautiful iris brooch by Louis

Comfort Tiffany, included in this exhibit, showed off Montana sapphires,

proving at the time that America had gem-quality minerals and you didn’t have

to go farther afield.”

EMPHASIZING THE EXTRA SPECIAL

The Nelson-Atkins exhibit concentrates on the specific time

frame that starts with the first world’s fair held in 1851 in London, organized

under the auspices of Prince Albert and Henry Cole, and ends with the 1939 New

York World’s Fair. “The reason we end with 1939 was because after that you had

World War II, so there’s a big gap before the next one was held,” explains

Futter. “But also, even by 1939, world’s fairs started to focus less on objects

and more on ideas. So we felt 1939 was a logical break.”

Illustrating the range of unique items on view at the fairs,

the exhibit presents 200 decorative objects, 19 of which are jewelry. While the

curators tried as much as possible to display the actual object that was

exhibited, sometimes the item shown is the same model. And in a small number of

instances, a representative piece “stands in,” says Futter, for a manufacturer

or a particular technique shown at a fair.

The exhibit is divided into five chronological periods:

1855-1873, 1876-1897, 1900-1911, 1915-1925, 1929-1939. But within those

categories, says Futter, there are thematic divisions that include

“technological innovation and revived techniques, nationalism, cross-cultural

influences and historicism. Jewelry can be in more than one section — most of

the objects in the exhibit tell multiple stories.”

A HAND’S-ON APPROACH

“We looked at literally tens of thousands of things,” says

Futter. “I think every one of the objects in the exhibition invites visitors to

learn more about them. And once you do, they become even more intriguing.”

Because world’s fairs themselves were interactive, says

Futter, the Nelson-Atkins installation is also interactive. Included are

vintage stereoscopes and View-Masters people can experience firsthand as well

as twenty-first-century 3-D technology where participants can virtually handle

objects and view short films detailing their importance.

In the gallery devoted to works from around 1900, a low-tech

interactive display allows visitors to view their reflections in a three-sided

mirror “wearing” the Tiffany & Co. iris brooch, or Jean Fouquet Art Deco

brooch (shown below), the Castellani diadem or a Lalique grape necklace.

JEWELRY CHOICES

To bring the best examples to the exhibit, the curators

reached out to museums, dealers, collectors and companies that were the

original exhibitors. “The Carnegie had an aluminum and gold bracelet which,

while it probably wasn’t exhibited at a fair, illustrates the fact that

aluminum was used in jewelry. There are local collectors here who owned some of

the historicist jewelry that we borrowed. Some of the circa-1920s jewelry was

lent by New York City jewelry dealer Lee Siegelson. The Walters Art Museum in

Baltimore was another source — Henry Walters bought pieces at the Paris

1889 fair, including the Tiffany iris brooch and, in St. Louis in 1904, the

Lalique plique-à-jour pansy brooch and the Lalique grape necklace. Tiffany

& Co. also was a very generous lender,” says Futter.

The names of the designers who exhibited at these fairs reads

like a who’s who of the jewelry world. The exhibit pays homage to them with an

array that includes a Lalique “wasp” stickpin, a Fabergé tiara, a Cartier Art

Deco Egyptian faience belt buckle with diamond accents, a Georges Fouquet

corsage ornament and a Maison Boucheron bracelet that shimmers with pavé

diamonds.

A VALUABLE PEDIGREE

Does having been exhibited at a world’s fair add to the

luster — and value — of jewelry? Perhaps. “I think in the past ten years,

there’s much more of a consciousness about world’s fair provenance,” says

Futter. “Before that, people were ‘oh, that’s nice.’ But now there’s a

heightened awareness of something that was shown at a world’s fair. And it’s

definitely elevating the prices of all sorts of decorative arts. Just recently,

in January 2012, there was a matchsafe sold at Christie’s. Because it had been

exhibited at the Paris Exposition of 1889 and it was quite lovely — in the form

of a stylized Native American raven’s head with semiprecious stones and inlaid

mother-of-pearl — the price it sold for was very strong. If you look at auction

catalogs now, they will say, “shown at a world’s fair.’”

According to Siegelson, who lent several pieces to the

exhibit, “The world’s fairs brought together the best examples of art and design

with advances in science, architecture and technology. Thousands of visitors

toured the exhibitions. Designers such as Cartier, Boucheron and Templier pushed themselves to create masterful designs. The

world’s fair venue freed the artists from making jewelry for consumption and

gave designers the opportunity to create beautiful jewelry and objects that

showed the skill of the maker. The pieces exhibited at the world’s fairs are

valuable today because those that survived are often the absolute best examples

of the era.”

“Inventing the Modern World: Decorative Arts at the World’s

Fairs 1851–1939,” runs at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City,

Missouri, through August 19, 2012; at the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh,

Pennsylvania, from October 13, 2012 to February 24, 2013; New Orleans Museum of

Art, April 14 to August 4, 2013 and The Mint Museum, Charlotte, North Carolina,

September 22, 2013 to January 19, 2014.

Article from the Rapaport Magazine - July 2012. To subscribe click here.